“My shirt is ragged and my pants are tore.

I ain’t found nothin’ I’m a-looking for,

And I want to go back to Baltimore….

Good old Baltimore.”— lyrics from a country song recorded in 1954 by Sonny James

In 1910, when visitors would come to call on Confederate Veteran George Watts, he would “[rise] from a rickety chair” and receive them with a “sweeping” bow.[i] “Old Man Watts, the [house] painter,” as he was known, was the embodiment of that Baltimore, that old Maryland, which Alabama native and wife of F. Scott Fitzgerald, Zelda Fitzgerald, described as “very polite.” That Baltimore was regarded as a Southern city by most Americans. And Baltimoreans themselves until more recently did not consider their city Mid-Atlantic or Northern. The Baltimore American advertised itself as The Daily Newspaper of the South; the Hotel Rennert, its bar and lounge the haunt of –some would say[ii]—Baltimore’s most famous resident, H. L. Mencken, boasted that it was The Palace of the South. Still taking pride in its heritage in the late forties, Baltimore raised a monument to memorialize Lee and Jackson’s last meeting. And, as late as the era of hula hoops and rock n roll, the town had not completely lost its Southern ways and manners. A buyer for a dress shop who traveled to the city frequently in the fifties recalled that it was charmingly rundown, slow-paced and “friendly.” But that “amiable” and soft-spoken old port that Francis Beirne, a Virginian, wrote about in 1951 would soon be gone.

Beginning in the late 1700s, Baltimore became the destination for multitudes of immigrants from all across Europe—New Orleans was to have her Stanley Kowalski, Baltimore, her Polock Johnny. In the early 1900s there was a migration of people from the rural Southland to “Up-South” Baltimore, a phenomenon that would enrich the city’s culture because it was not at odds with it; a dramatic post-centenary decade resettlement of Northeasterners would cleanse that culture, however. These days the town that was once famous for her Southern cooking—the Rennert was renowned for its beaten biscuits, an old Maryland tradition—now finds Southern food a novelty: The Baltimore Sun runs feature articles on the city’s “black cuisine,” calling such dishes as sweet potato pie soul food when this holiday favourite is merely old-time Maryland cookery. A further indication of cultural decay, the Upper South dialect of the old Baltimoreans has gradually been replaced by an unpleasant admixture, though some Southern pronunciations and expressions such as “right smart” are still heard.

By the 1850s, the resentment of Baltimore citizens towards the newcomers was reaching the boiling point. And in 1856 they elected the nativist Thomas Swann to the office of mayor. But four years later, Baltimore had grown tired of the Know-Nothings (who had also enjoyed some brief success in Kentucky), and George William Brown, the reform candidate, would be elected to succeed Swann. Unfortunately, Brown’s term would end unceremoniously with his arrest in 1861 by Yankee troops occupying the city.

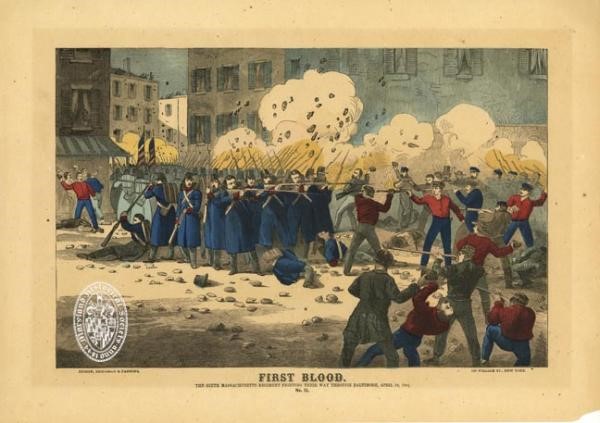

Though, like the rest of the Borderland South, Baltimore’s German population was strongly unconditional unionist in temperament, the city was far from a Republican stronghold. Despite the fact that after Lincoln’s troops took possession of the town, Beast Butler trained his guns on its citizens, the Southern underground flourished. Fannie Beers, the wife of a Confederate soldier, after passing through the city during the war, remarked that the Baltimoreans were filled with ardent love of “the Cause,” and “bitter hatred” for the Yankees—Butler raged against these “secesh” and their defiance and threatened to raze their town.

Mencken, reflecting on the conflict between North and South that had ended just fifteen years before his birth, considered the Southern cause to have been necessary and just, this surprisingly from a relativist who once wrote that “if [he had known] what was true,” he “probably” would have been “willing to sweat and strive for it…to the tune of bugle-blasts.” Mencken’s sympathy with the Southern struggle for independence and his professed admiration for the gentry’s refinement and elegant way of speaking, notwithstanding, he never seemed truly to understand the region, a region to which “his own” state belonged. He referred to the South as “down there.”

The product of the insularity of Baltimore’s burgeoning ethnic neighborhoods, the Baltimore Ghetto in the words of one Southerner he had offended, Mencken, the son of German immigrants, in fact spoke like someone from Kalamazoo, Michigan, not Baltimore. [iii] He was not loved by the people of Crab Town or other Marylanders. Baltimoreans, to the surprise of Mencken and the management of the Sunpapers, had great affection for their country kinsmen, resorting to boycotts, angry letters and civil unrest after Mencken in a 1931 editorial, which rightly condemned the actions of a lynch mob near Salisbury, appeared to place the blame for the actions of these vigilantes on the entire Eastern Shore and all of rural Maryland.

The anti-agrarian Sage of Baltimore railed against an electoral system which allowed the people in the provinces to nullify the votes of those he admired. The improvement of these remote and benighted areas, in Mencken’s opinion, was best left up to city men such as the president of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad and the head of Johns Hopkins University, both natives of Vermont, and communist attorney Bernard Ades,[iv] the son of Russian-born immigrants (during the Spanish Civil War, he joined the Abraham Lincoln Brigade). Mencken even suggested a missionary crusade to educate some of the peasantry.

Mencken would not live to see it, but as he had hoped, his city men, his New Baltimoreans, along with the D.C. suburb dwellers, mostly carpetbaggers, would begin to disenfranchise the much-despised “morons” and “whooping soul-savers” living on the Eastern and Lower Western Shores and up in the Piedmont just under the Mason-Dixon. Old Crab Town, against seemingly impossible odds, had held on to its Southern traditions and had spoken its Upper South English right up to the Cold War era when the city would begin its rapid cultural decline. Though it still has les beaux arts—its award-winning symphony and acclaimed Walter’s Gallery—Baltimore, which is now awash in illegal immigrants, is a charmless hybrid with a third-world murder rate.

[i] “Last Survivor of a Gallant Band,” The Evening Sun, Baltimore, August 27, 1910.

[ii] Others would argue that the city’s most renowned resident was Edgar Allan Poe.

[iii] Interview with Donald Howe Kirkley, 1948.

[iv] “The Eastern Shore Kultur,” The Evening Sun, 7 December 1931. “Sound and Fury,” The Evening Sun, 14 December 1931.

Beautifully done. What a pleasure. Thank you and Merry Christmas!

Merry Christmas to you also, Leslie.

Very well written and enlightening, thanks Joyce!

Thanks, Terry!

Sadly, many areas are experiencing what Baltimore has gone through. Minneapolis, Saint Paul and other much smaller towns.

Worthy article. Merry Christmas to all. Say. Hello to my kin if out on the streets of Abbeville.

Thanks for your comment, Gunny! Much appreciated. Joyce