Originally published at barelyablog.com

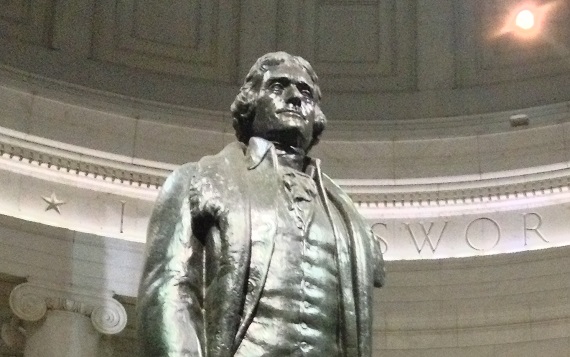

In the mid-1950s my family arrived in Athens, Alabama, I being eleven, my father a mathematician working at the Army Ballistic Missile Agency in nearby Huntsville. Athens was small, the county seat of Limestone County. The town square had the courthouse in the middle with the statue of a Confederate soldier and a Baptist church. The library was a frame building with many books and, at least in memory, a musty smell and there was Athens College, now grandiosely Athens University.

The age was politically fraught after Brown, though I didn’t know it. The South was then under siege, isolated, ingrown, defiant, idiosyncratic, tightly segregated, and determined to keep it that way. It was what it was and liked it–a land of guns, NASCAR, hot rods, dogs, and defined sexes. Dixie was the only pungent, culturally distinctive part of the country outside of New York City. An American Sicily, it shaped American music. Gospel, Southern blacks. Blues, Southern blacks. Cajun, Southern whites. Zydeco. Dixieland jazz, Southern blacks and whites. Bluegrass, Southern whites. Country, Southern whites. Rockabilly, Southern whites. Rock, Southern blacks and whites.

There was a regionalism, the attachment to the battle flag, a profound locality which amounted to “Fuck you and the horse you rode in on,” a residual, hopeless rebelliousness against the crushing power of the North.

The times were looser then, less hectored and watched. Rules were few because people knew how to behave without them. Athenians supervised their own lives and it seemed to work. The dog went out in the morning, visited such places as she thought fit and came back when it suited her. Nobody cared. It was what dogs did. We kids went barefoot, supporting the minor agony of the first week until our feet hardened to leather. In summer nothing seemed hurried. Barefoot and BB-gunned, we went forth on glowing green mornings to see what adventure offered.

Small boys carried pocket knives everywhere because no one could think of a reason why not. There was no telling when you might need to sharpen a stick or put notches on a spool tank for traction. Teachers ignored pocket knives, though they waxed wroth over the passing of notes. BB guns were part of our anatomy, like an extra arm. There were two varieties. The plebeian Red Ryder, plain, dark brown, and functional, for four dollars, and the patrician Daisy Eagle, with plastic telescopic sight, for I think eight. Both were lever-action. They were an accepted part of society. Every corner store sold round cardboard tubes of a hundred BBs which we poured rattlingly into the barrel. Nobody thought twice about this. When you went into Limestone Drug, you left your BB gun in the corner. But more of that shortly.

In Athens in a minor valley there was the appropriately name Valley Gin Company. It was the kind of gin that took seeds out of cotton, not the kind making vodka unpalatable by the addition of juniper juice. It was of corrugated iron, run down like so much of the South, and abandoned except in cotton-picking time. There was much brush around and a creek ran through the valley, crossed by an iron foot bridge.

Here I came on the long afternoons of the Southland to lean over the bridge rail and shoot water moccasins. Actually I think they were harmless water snakes but water moccasins better caught the spirit. There is such a thing as too much truth.

In the cool and shade of what is now another world, minnows sparkled in clear water and dragonflies flitted in metallic blues and greens. We knew them as “snake doctors,” though elsewhere they were “the devil’s darning needles,” or “mosquito hawks.” They were fast, agile, ferocious looking and I often tried to shoot them, but never with any luck.

The years with a BB gun would not be entirely without benefit. Discharging the shiny little balls against the sky, watching the coppery glint recede through the air, we developed an eye for windage and elevation, that lives later in Marine boot camp would make me the only recruit in a platoon of city kids who could shoot, and this avoided much punitive labor.

The South had not recovered from the Civil War and, along with a middle class like any other, there was poverty. A few kids had teeth blackened with decay and one that I remember had to have his entire dentition pulled. My friend Charlie Cox lived in a shack with a light bulb dangling on a wire. Athens was the county seat of Limestone County and so comparatively advanced but in nearby Ardmore County, if memory serves, instead of summer vacation kids got off at cotton chopping and cotton-picking time.

The Limestone Drugstore was on the town square, and still is, across the courthouse and the statue of the Confederate soldier. It had the usual things one has in a drug store but also several marble-topped round tables and accompanying chairs, a soda fountain with pimply soda jerk, and a large rack of comic books. The Limestone was not a Northern chain, impelled by cutthroat acquisitiveness from corporate in New Jersey, and so was relaxed. The owner, or so we thought he was, was an old man in his seventies we all knew as Coochie, with frizzy red hair. He liked little boys. Not lasciviously as would be suspected today. He just liked kids.

I think Coochie used the comic rack as bait. Probably in all its years the Limestone never sold a comic book, or tried to. We came in, a legion of eleven-year-olds, and piled our BB guns and fielder’s mitts in a corner. It wasn’t a rule, but have you tried to read Plastic Man while holding a BB gun, baseball glove, and cherry coke? We grabbed several comics, by now crumbling and settled in. We spent hours deep in Batman, Green Lantern, Superman. It probably improved our reading, but I don’t know. I can still name Superman’s girlfriends, Lois Lane, Linda Lee, and Lana Lang, as well as Jor-El and Lara, and three different colors of kryptonite. Don’t tell me we wasted our time.

Athens Elementary, where I went to sixth and seventh grades, was not yet integrated and so had none of the problems that would soon come. The teachers were college-educated women, these not yet being siphoned off into biochemistry. They believed their job was to teach the Three Rs, as did teachers all across America then, as well as history, the sciences, and so on. There were no discipline problems to amount to anything though the Board of Education, a substantial paddle, existed to ameliorate the aborning ardor of adolescence. I once fell afoul of this instrument. It didn’t come to much.

The South did not know what to do about the Negro. His dark face loomed over everything. Integration was coming, and people knew what it would do. It did. Segregation couldn’t last, but integration couldn’t work. This left few possibilities.

At the time, virtually no contact between races existed. The water fountains on the town square said White and Colored, the bathrooms in gas stations, Men, Women, and Colored. It the movie theater, known to us as the “pitcher show,” blacks sat in the lower right-hand seats. I barely remember seeing Negros and to this day I don’t know where the black school was. About this time Emmett Till was beaten to death by Klan wannabes in Mississippi. Most people were decent. Some weren’t.

Crime did not yet exist, though it does now. Children could roam wild until late on summer nights with no hazard. A favorite haunt was the Kreme Delight a soft ice cream stand in the style of, who would have thought it, the Fifties. On summer nights yellow neon buzzed and so did bugs attracted by them and children attracted by the ice cream, though we didn’t buzz. Kreme Delight is still there. We got spiral swirls of chocolate or vanilla and felt independent in the night though of course we weren’t. If Annette Funicello had appeared and asked for a double malt, she would have fit. Young studs in their late teens drove around in fitty-six Ford convertibles, hair slicked back in tidal waves, cigarette dangling from corner of mouth, approaching manhood, well aware of it, and maybe trying to hurry things a little. Hopped-up mills, bad-ass V-8s, idled potato potato potato maybe, not really hopped up but with a hole in the muffler but it was close enough. Nothing is better than driving around the gathering point with your best girl and a noisy motor and hoping you look like Elvis. With me it was Hojo’s in Fredericksburg, Virginia years later, but the principle doesn’t change. Or if it has, we’ve lost something.

The South had much on its conscience regarding the Negro. One day Northern cities would have sprawling, semiliterate, segregated ghettos where there would be thousands of blacks killed every year, poverty, drug addiction, phenomenal crime, but these were in the future. Now it is the North that does not know what to do. Some Southerners might say, let them choke on it.

Having no more orality than is good for a small boy, I figured out how to steal twelve-gauge shotgun shells from the country store near our house by putting them in the center of a roll of toilet paper and buying it. I do not know what disease the store’s owner thought might afflict my family. We then cut the shot charge from the shell with a Buck knife—as mentioned, small boys then routinely carried pocket knives with no ill effect, unless you were a twelve-gauge shell of course. We then put the powder charge on the end of a BB gun barrel , shot the primer, and–fwoosh!—a most satisfying spray of sparks erupted.

We were probably dangerous. At least I hope we were. We took bicycle spokes and pressed match heads into the cavity, followed by a piece of birdshot, and held a match under the ensemble. A satisfying snap! Followed. I think this an important chapter in the history of American ordnance. There was a way, too complex to explain here so it will be lost forever, to turn a clothes pin into a gun that will shoot a flaming kitchen match for at least three feet. Do not think that we misspent our time.

My family first lived in a big decaying house on Pryor Street, near the country store. I was for some time known, mostly in jest, as the “Dam Yank on the corner,” until I learned the soft Rococo accents that God meant us to use. People didn’t like Yankees. I guess I still don’t if it means morally pretentious New Englanders. Hitchhiking years later in the humid stillness of the Mississippi Delta, where speech flowed slow and sweet like Karo syrup dripping on busted China, I decided the language had reached its pinnacle of dignity and humility. But Alabama was close.

My parents were Cavalier Virginians from Southside and knew participles from gerunds. My mother once asked one of my friends whether he would like to lunch with us. With curtsey native to the state, he replied, “No, thank you, Ma’am. I has done et.” She was horrified. Other elocutions were, “You ain’t got the sense god give a crabapple,” and, “do that again and I’ll slap the far outa you.” Fire. Sometimes it was “slap the livin’ dogsnot,” but that is rude, so we will omit it here.

A high point of my young life, or at least a point, was the discovery of the science building of Athens College, where my father taught chemistry as a sideline. The building wasn’t locked. In the library of the college in the encyclopedia Britannica I found the formula for thermite, a fearsomely high-temperature incendiary. (If interested, powdered aluminum and iron oxide. It proved effective for burning Tokyo should you ever need to do that.) Anyway, I found the materials in the science building. Perry James, son of the college president, and I put some in his mother’s prize frying pan, thinking if immune to high temperatures. The resulting hole caused…well, it caused.

Being something of a mad scientist, I made rockets that didn’t work with zinc, sulfur, and stolen potassium permanganate, invented the mnemonic prometanatel, for prophase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase. This has not materially furthered my trajectory through life, but neither has it done harm. Free access to a science building has much to recommend it.

Athens was a monoculture and so at peace with itself. The kids had names like Jimmy-jack ‘Callister, Sally-Carol Jenkins, Johnny Loggins, or Billy-Joe Faulkner. There were exceptions, such as Sanders Dupree and my buddy Don Berzette, but these were few and, I think Protestant like us. Athens was in the Bible Belt and everyone took it seriously or at least went with the current. The parts about fornication may have received less intense attention than others among teenagers but I don’t know because I wasn’t one. But I suspected. All were white. There is something to be said for this.

Ages later, on a mountain side in Peru while working as a journalist, I ran into a National-Guardplatoon from Athens. Did they know Don? I asked. Yep.

My family left Athens after a couple of years. Sputnik had gone into orbit and was saying beep beep humiliatingly. This couldn’t be tolerated. Desperate effort had gone into getting a Jupiter C rocket also into orbit. My family went to Redstone Arsenal to see a celebratory mockup. It was wickedly cold and a determined patriotic model in bikini stood grimly by the exhibit. Sputnik had the salutary effect of raising salaries for mathematicians and my father, a loyal son of the South, got a better deal at Dahlgren Naval Proving Ground, as it was then know, in rural Virginia. I have ever since thought well of the Russians.

Note: The views expressed on abbevilleinstitute.org are not necessarily those of the Abbeville Institute.

The South was not right because it was righteous, but because it was honest. It accepted its sins, because it understood repentance. Unlike Yankees, it did not blame its sins on others and claim to be washed clean.

I stopped reading Reed after he supported the unjust sentencing of those people who protected their lives against a thug.

I grew up in the North, but in a small town with farms nearby and Fred’s commentary here is of a childhood I can remember there.

Fred’s article brought back many memories of a nine year old growing up in a tiny textile town in North Carolina. Though I did not grow up on a farm, my uncle was a local cotton farmer and I vividly remember picking cotton in the early 1950s. I also remember the local drugstore with the myriad of comic books. Like Fred, all of boys had our BB guns, heck, every kid in the area had one and we got pretty good with them. One of my vivid memories of of the time when my best buddy found some 22 cal cartridges and we bet on who could hit one, placed properly on a rock, with a BB from about 20 feet away. My buddy was a better shot and hit it the first try, with the alarming result that the spent cartridge flew back at us and hit him on the left cheek, burning a permanent rectangular scar. No more of that, but I must admit, it was fun!

I hope the F bomb and Playboy acolytes aren’t going to be a featured part of this blog. Decidedly un Southern and definitely a disappointment. Not what we’re about.

Great article, Fred. It was filled with memories of my childhood, almost a carbon copy. I was raised on a truck/tenant farm in Tidewater, Virginia, also Princess Ann County, which is now Virginia Beach. And no, we didn’t grow trucks on our farm, but we did grow a variety of vegetables and greens. Unlike Fred, I had limited contact with white children until I attended elementary school at age six. Until then, my only playmates were black children living on our farm. On rare occasions I would travel to Norfolk, VA, so I could play with a distant cousin. Segregation locally was much the same as the rest of the South. Integration of the lower schools started in the late 1950’s, and by that time I was in college, so I was not personally involved. I am very familiar with the chemical jargon since I have a B.S. in chemistry, and carried the interest a little further while serving in the USAF for 20 years as an Explosive Ordnance Disposal technician. Still Fred, your thoughts brought to words were spot-on, and reflected the childhood of many Southern children, as it did mine. Thank you for taking the time to project it to the outside world.