There is a dichotomy to how people view Jesse James. While some have viewed him as a murdering thief, others have argued that he was like a modern-day Robin Hood. To really understand the man requires an examination of his life and an honest analysis of the events that shaped him in Missouri.

WHO WAS JESSE JAMES?

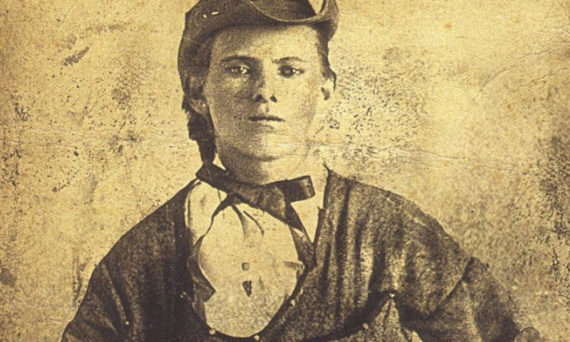

Jesse James was born in Missouri on September 5, 1847, just seven years before the Kansas-Nebraska act of 1854. His father, Robert James, was a Baptist pastor and died when Jesse was just three years old. Robert was a man of learning and left behind fifty-one books in his will that dealt with math, chemistry, theology, astronomy, grammar, Latin, Greek, public speaking, philosophy, history, literature, and other subjects. By 1850, Robert James outright owned 275 acres of land and had also helped found William Jewell College. The James farm had thirty sheep, six cattle, three horses, a yoke of oxen, and seven slaves. These facts show that Jesse James was not some backwoods yokel lacking a good upbringing, but was fairly well educated knew right from wrong.

In fact, Jesse’s older brother Frank loved reading and quoting Shakespeare, while Jesse preferred to read and quote the Bible. Jesse was known to sing in the choir and was reputed to have always treated women in a gentlemanly fashion. Some accounts say he did not drink alcohol or use bad language, and he was noted for being extremely loyal to kith and kin.

HOW MISSOURI AND “BLEEDING” KANSAS SHAPED HIM

The violence in Missouri and Kansas before and after the War Between the States was an important part of Jesse’s development. After the Kansas and Nebraska Acts of 1854, various groups labeled Free Soilers, Jayhawkers, Red Legs, Radical Republicans, and Abolitionists flooded the border of Kansas and Missouri with the goal of disrupting the national balance of power in favor of the “free states.” Their initial goal was to prevent any Southern people from entering Kansas, but they also went on raids in Missouri to attack Southerners and take their property. Any Southerners from Missouri that traveled to retrieve their stolen goods in Kansas were promptly killed.

Even though Southerners are typically labeled “border ruffians” during this period in most popular histories, it was the Northern groups in Kansas that took the violence to another level and mutilated men from the pro-Southern camps. John Brown’s actions at the Pottawatomie massacre are just one example of the barbarous acts committed by these radical abolitionists.

When the first elections in Kansas Territory were held in 1855, the results were overwhelmingly pro-slavery. The free state settlers refused to accept this and held their own elections, having even set up their own legislatures by 1856. They then started building abolitionist newspapers and a massive military fortification known as “The Free State Hotel.”

President Franklin Pierce reasoned this free-state legislature unlawful and called for arrests. A group of abolitionists attempted to assassinate a sheriff in Lawrence, Kansas to prevent these arrests. In response, Federal Marshall Israel B. Donaldson led a posse of hundreds of Southerners into Lawrence, where they destroyed the newspapers and “Free State Hotel.” No abolitionists were killed during this event.

The Democratic Platform, a newspaper from the time, printed the following in response to the border violence:

“Kansas must be a slave state if half the citizens of Missouri had to emigrate there with musket in hand, prepared to die for the cause. Shall we allow such cutthroats and murderers to settle in the territory joining our own state? No, if popular opinion will not keep them back, we should see what virtue there is in the favor of our arms.”

The idea of “Bleeding Kansas” usually conjures up images of political cartoons with slavery being forced down the throat of free soilers. But these ideas are misleading, and the free soilers were more opposed to competition for white labor than they were about the morality of slavery. The Republican Platform of 1856 is also ample evidence that the North intended to overturn the elections of Kansas and keep it open exclusively to free whites.

Southerners who rushed to arms were merely defending their own homes, and Union sources from the time prove this. Major A.V.E. Johnson of the 39th Missouri’s federal troops declared that he would “devastate the country and leave the habitations of Southern men not one stone upon another” and that “extermination in fact was what they [Southerners] all need.”

Kansas Senator James Henry Lane, who went on to be a Union general, said: “Missourians are wolves, snakes, devils, and damn their souls – I want to see them cast into a burning hell. We believe in a war of extermination. There is no such thing as Union men in the border of Missouri. I want to see every foot of ground in Jackson, Cass, and Bates Counties in Missouri burned over and everything laid waste.” Lane also wrote George B. McClellan and proposed that any disloyal white rebels could have had their lands taken and given to loyal blacks.

JAMES DURING THE WAR BETWEEN THE STATES AND RECONSTRUCTION

By June 1861, federal troops under Nathaniel Lyon captured Jefferson City, ejected the lawfully elected officials, and set up a military government. James’ family maintained strong Southern sympathies and his brother Frank joined the Confederate ranks early on in 1861. Frank fought at the Battle of Wilson’s Creek and later returned home because of illness.

The legend holds that in May of 1863, Jesse was at his plow when Union men came searching for information about Confederate forces. The soldiers attacked Jesse and partially hanged his stepfather, Dr. Reuben Samuel, several times from a tree. At the end of this encounter Jesse was badly beaten, his mother was thrown in jail, and his stepfather was inflicted with serious brain damage.

Jesse then went on to join the Confederate guerrillas and participated in several violent, effective raids against Union forces. Confederate guerrillas were so successful that Union general Thomas Ewing issued two proclamations to try and stop them. His General Order 10 made it a crime punishable by death to aid Confederate soldiers, and General Order 11 stated that all Missourians within certain counties had to report to Union camps or leave the state. The chaos which ensued was captured in a famous painting by George Caleb Bingham, who served in the Union army and vehemently disagreed with Ewing:

General Order No. 11

Acts like these actually resulted in greater sympathies for Confederates. George Caleb Bingham described the Union soldiers as having actually killed men in the act of obeying the General Orders and stealing their effects from wagons. Southerners were massacred and even children were shot in the arms of their families.

Sadly, the murder and theft that happened as a result of General Order 11 was not an isolated incident and these savage acts had been perpetrated against Southerners since 1854. One Red Leg officer described the destruction by saying his men burned one hundred and ten houses, worth about $20,000 each. And that was just one group of Union soldiers, causing what would be (in today’s dollars) tens of millions of dollars worth of property damage.

At the end of the war, Jesse was shot while attempting to surrender and spent some time trying to recover. He eventually returned home and tried farming, but the new bayonet government complicated things. A Senator from Missouri, Charles Drake, drafted a new state constitution. Under the Drake constitution, former Confederates were disenfranchised, former slaves were given the right to vote, and segregated public schools were created. It also held that a new “Ironclad Oath” would be instituted to keep only Union loyalists as judges, teachers, lawyers, and pastors.

Hundreds of state officials were purged from their posts, and radicals jailed justices that declared Drake’s actions unconstitutional. Some sources show that in 1866, some 4,000 Southerners were killed in Southwest Missouri. By 1867, former Confederate guerrillas were basically wanted dead or alive. Jesse and his gang resorted to robbery because the Union’s military government had made an honest living impossible.

Jesse James’ early robberies were all small, and he was first mentioned in a newspaper after the robbery of Daviess County Savings Bank in Gallatin, Missouri. Jesse reportedly thought the bank’s cashier was the Union soldier that had killed Confederate “Bloody Bill” Anderson, so Jesse shot him. This was seen as an act of vengeance in the public eye and built on the James’ already prominent reputation. The James gang worked with other groups to commit twenty-five robberies and an equal number of murders, but not all of these are directly attributed to Frank and Jesse.

THE REASON JESSE JAMES IS NOT A ROBIN HOOD

Jesse James has been compared to Robin Hood since about 1870 when James originally started writing John Newman Edwards, the editor of the Kansas City Times. John Edwards was a Confederate sympathizer, and Jesse wrote him many letters defending the James gang’s actions and declaring their innocence. Edwards began portraying James as a Robin Hood figure, but the comparison has been perpetuated by famous American writers like Carl Sandburg.

The fact is that Robin Hood is a myth, and Jesse James was very real. Comparing James to a fictional character takes away from the complex history that shaped him. There’s no evidence to show that James distributed any of his loot to the poor. However there are some claims that he would not rob former Confederates, and some papers defended his actions as honest. For example, the Lexington Caucasian newspaper on December 12, 1874 defended Jesse James’ gang after a robbery by saying:

“The funds seized by the bandits were just as honestly earned as the riches of many a highly distinguished political leader and the railroad job manipulator.”

These various interpretations make James more difficult to categorize. He was not some common criminal or Robin Hood, but more of an “outlaw” or “vigilante,” both of which had different meanings than they do today.

Being a vigilante in James’ day legally meant the creation and enforcement of laws by organized extra-legal groups in the absence of law enforcement. Vigilantism basically started with the Regulator movement in the pre-Revolutionary backcountry of the Carolinas. Just as the Regulators took the law into their own hands when the British Royal Government would not protect them, so too did Jesse James when Union soldiers plundered his homeland. Clearly, this type of vigilante is not the same image we see depicted today in movies like Death Wish, where vigilantes indiscriminately kill criminals despite capable law enforcement.

Interestingly, Webster’s definition of outlaw in 1828 was “A person excluded from the benefit of the law or deprived of its protection.” James, as a Southerner and Missourian growing up in his day, had been basically on the run from federals since his teens and was never protected by the law. In 1875, Pinkerton agents allegedly firebombed the James family home. The explosion blew off the arm of Jesse’s mom and killed his half-brother. All of these factors show that Jesse James was not just an “outlaw,” but someone that the government conspired against and never deemed worthy of a fair trial.

By this definition of the word, Southerners are technically outlaws right now because we are deprived and excluded from the protection of the law when our monuments and history are allowed to be illegally torn down. The way people interpret history is becoming too complicated and, ultimately, it is irresponsible and intellectually lazy to refer to Jesse James as a Robin Hood figure. If the critics and fans of James took the time to investigate his motivations, it would be clear that Northern and Union depredations made James into the “outlaw” he was. Had the federal government not perpetuated lawlessness and violence in Missouri for two decades, Jesse might have grown up to be a completely different person.

Making a visit to the James’ Farm is on my list of things to do. Jesse James for all of his faults is still one of my favorite Southerners. Top 10 for certain.