Critical to the debate regarding the right of secession is where, in the minds of the founders, did sovereignty reside. Were the States sovereign principals and the federal government their created agent? Or was the federal government sovereign and the States its created agents? State sovereignty prevailed for most of the 70 years after the founding, but political prejudice and sectional interests continued the debate after the founding generation had passed and certainly clouded the issue in these United States. To escape the clouds it is helpful to listen to foreign statesmen whose tradition of understanding the US government reaches back to the time of the founding without the intervening political and sectional influences.

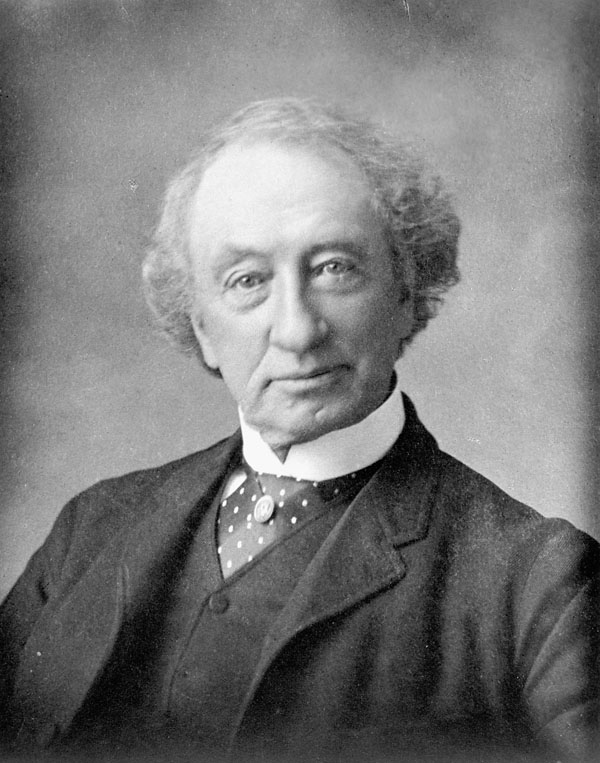

It is interesting to note the opinions of our Canadian neighbors to the North regarding what kind of government the US had when founded. Here is how future Canadian Prime Minister John A. Macdonald described the US union in 1864:

“It has been said that the United States Government is a failure. I don’t go so far. 0n the contrary I consider it a marvelous exhibition of human wisdom. It was as perfect as human wisdom could make it, and under it the American States greatly prospered until very recently; but being the work of men it had its defects, and it is for us to take advantage by experience, and endeavor to see if we cannot arrive by careful study at such a plan as will avoid the mistakes of our neighbors. In the first place we know that every individual state was an individual sovereignty – that each had its own army and navy and political organization – and when they formed themselves into a confederation they only gave the central authority certain specific rights appertaining to sovereign powers.” (Quebec History, Comparing Canadian and American Federalism, Claude Belanger, Department of History, Marianopolis College)

Sounds like a very Jeffersonian description of State sovereignty that our far North neighbors recognized in our founding.

In 1864, leaders of the Canadian Provinces met to discuss whether they would form a union, and whether that union would be federal (decentralized) or legislative (centralized). In considering their own union they discussed the pros and cons of the US union. Again we hear John A. Macdonald, who wanted a strong central government as Lincoln was warring for in the US at the time, but he concedes that such would intrude on the unique freedoms and independent cultures that each Province represented:

“Now as regards the comparative advantages of a Legislative (centralized) and a Federal (decentralized) union, I have never hesitated to state my own opinions. I have again and again stated in the House, that, if practicable, I thought a Legislative Union would be preferable… But, on looking at the subject in the Conference, and discussing the matter as we did, most unreservedly, and with a desire to arrive at a satisfactory conclusion, we found that such a system was impracticable. In the first place, it would not meet the assent of the people of Lower Canada, because they felt in their peculiar position – being in the minority, with a different language, nationality and religion from the majority – in case of a junction with the other provinces, their institutions and their laws might be assailed, and their ancestral associations, on which they prided themselves, attacked and prejudiced; it was found that any propositions which involved the absorption of the individuality of Lower Canada – if I may use the expression – would not be received with favour by her people… Therefore, we were forced to the conclusion that we must either abandon the idea of Union altogether, or devise a system of union in which the separate provincial organizations would be in some degree preserved.” (Quebec History, John A. Macdonald, Confederation and Canadian Federalism, Claude Bélanger, Department of History, Marianopolis College)

Once more the wisdom of Jefferson is reflected in the recognition that State (and Provincial) governments best represent their unique polities and therefore America’s founding ideal of a government by consent of the governed. The danger of Lincolnian centralization is that it makes the unique values and freedoms of the people of a State vulnerable to majorities outside the State. While Canada certainly settled on a more centralized form of government, they do allow Provinces to nullify certain actions of the central government, and they allow Provinces to consider secession without turning the guns of the central government upon them!

Now for those who think Canadians had no intimate connection with America’s founders, consider the following. In a letter written by the First Continental Congress, the people of Quebec were invited to give themselves representation and send delegates for the next continental Congress, to be held in Philadelphia on May 10, 1775. In this letter, the sentiment against centralized sovereignty and for States Rights is abundantly clear; as is the fact that it was the “Delegates of the said colonies….deputed by the inhabitants of the said Colonies” (later self-declared as States), who created the Union, and not an “aggregate of the people” as Lincoln claimed.

Hear the words of our Founders in this “Letter to Inhabitants of the Providence of Quebec“ as penned by Henry Middleton of South Carolina, President of the First Continental Congress (emphasis in the letter is mine):

“October 26, 1774,

Friends and fellow-subjects,

We, the Delegates of the Colonies of New-Hampshire, Massachusetts-Bay, Rhode-Island and Providence Plantations, Connecticut, New-York, New-Jersey, Pennsylvania, the Counties of Newcastle, Kent and Sussex on Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North-Carolina and South-Carolina, deputed by the inhabitants of said colonies, to represent them in a General Congress at Philadelphia, in the province of Pennsylvania, to consult together concerning the best methods to obtain redress of our afflicting grievances, having accordingly assembled, and taken into our most serious consideration the state of public affairs on this continent, have thought proper to address your province, as a member therein deeply interested… ‘In every human society,’ says the celebrated Marquis Beccaria, ‘there is an effort, continually tending to confer on one part the height of power and happiness, and to reduce the other to the extreme of weakness and misery. The intent of good laws is to oppose this effort, and to diffuse their influence universally and equally.

Rulers stimulated by this pernicious ‘effort,’ and subjects animated by the just ‘intent of opposing good laws against it,’ have occasioned that vast variety of events, that fill the histories of so many nations. All these histories demonstrate the truth of this simple position, that to live by the will of one man, or sett of men, is the production of misery to all men… On the solid foundation of this principle, Englishmen reared up the fabrick of their constitution with such strength, as for ages to defy time, tyranny, treachery, internal and foreign wars… In this form, the first grand right, is that of the people having a share in their own government by their representatives chosen by themselves, and, in consequence, of being ruled by laws, which they themselves approve, not by edicts of men over whom they have no control…”

It is unimaginable that these same founders would later create a Constitution that yielded sovereignty to the general government to “confer on one part the heighth of power.” The policy of the general government could then be shaped by an unchecked majority. By 1860, it was the Northern section of the country that held this majority, and was seeking to use it for sectional advantage. We were founded on a States Rights principle and that principle was why the Confederate States of America was created. The North was seeking to abandon this most essential founding philosophy. The South was seeking to maintain it:

“Northern States of a political school which has persistently claimed that the government thus formed was not a compact between States, but was in effect a national government, set up above and over the States…The creature has been exalted above its creators; the principals have been made subordinate to the agent appointed by themselves.” Jefferson Davis Message to confederate Congress April 29, 1861.

“I love the Union and the Constitution, but I would rather leave the Union with the Constitution than remain in the Union without it.” Jefferson Davis

“Under the favor of Divine Providence, we hope to perpetuate the principles of our revolutionary fathers” Jefferson Davis, First Inaugural.

“Forced to take up arms to vindicate the political rights, the freedom, equality, and state sovereignty which were the heritage purchased by the blood of our revolutionary sires” Jefferson Davis, 1863.

“The principle now in contest between north and south is simply that of state sovereignty” Richmond Examiner, Sep 11,1862.

“All that the South has ever desired was the Union as established by our forefathers should be preserved…” Gen. Robert E. Lee.

“We quit the Union, but not the Constitution—this we have preserved. Secession from the old Union on the part of the Confederate States was founded upon the conviction that the time-honored Constitution of our fathers was about to be utterly undermined and destroyed. ” Hon. Alexander H. Stephens to the Virginia Secession Convention, April 23, 1861.

“When the South raised its sword against the Union’s Flag, it was in defense of the Union’s Constitution.” Confederate General John B. Gordon.

Even a most quoted modern Leftist historian had to admit:

“The South’s concept of republicanism had not changed in three-quarters of a century; the North’s had. With complete sincerity the South fought to preserve its version of the republic of the Founding Fathers–a government of limited powers.” Professor James M. McPherson, Antebellum Southern Exceptionalism.

“Union victory in the war destroyed the southern vision of America and ensured that the northern vision would become the American vision. Until 1861, however, it was the north that was out of the mainstream, not the south.” Dr. James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom.

“The United States went to war in 1861 to preserve the Union; it emerged from war in 1865 having created a nation. Before 1861 the two words ‘United States’ were generally used as a plural noun: ‘The United States are a republic.’ After 1865 the United States became a singular noun. The loose union of states became a nation.” James M. McPherson. Out of War a New Nation, Spring 2010, /vol. 42, No. 1

And still today Canadians see what happened to the United States because of Lincoln’s bayonets:

“It would be fair to say… that Canada has become, since 1867, far less centralist while the US has become far more centralist.” Professor Claude Bélanger, Marianopolis College, Westmount, Quebec.