Editor’s Note: United States Senator Thomas F. Bayard delivered this speech in January, 1875 on the 60th anniversary of the Battle of New Orleans. Bayard, later United States Secretary of State, considered the military occupation of New Orleans to be an unconstitutional usurpation of power and a direct assault on republican government. He denounced Gen. Philip Sheridan, insinuated that President Grant was as corrupt as the “sham” government that presided over the State, and called on the American public to physically resist these actions by the Republican Party.

Mr. President: I call for the reading of the resolution now before the Senate, and of the amendment of the Senator from New York.

The Chief Clerk. The resolution is as follows:

Resolved, That the President of the United States is hereby requested to inform the Senate whether any portion of the Army of the United States, or any officer or officers, soldier or soldiers of such Army, did in any manner interfere or’ intermeddle, with, control or seek to control, the organization of the General Assembly of the State of Louisiana, or either branch thereof, on the 4th instant; and especially whether any person or persons claiming seats in either branch of said Legislature have been deprived thereof, or prevented front taking the same, by any such military force, officer, or soldier; and if such has been the ease, then that the President inform the Senate by what authority such military intervention and interference have taken place.

The amendment is to insert after the word “Senate” the words “if in his judgment not incompatible with the public interests.”

Mr. BAYARD. Mr. President, in my judgment the amendment proposed by the honorable Senator from New York to this resolution is quite out of place and unnecessary. The resolution itself, we all know as a public fact, was a mere formal preliminary to congressional action. It was an orderly and respectful call upon a co-ordinate branch of the Government to account for his apparent exercise of unlawful power. I do not now propose to debate the question raised by the amendment of the Senator from New York, not because it is not important in itself, and touches an interesting, grave, and substantial question, but because it is overshadowed by the main subject upon which it is now sought to be ingrafted. Nor, since I have been personally referred to by that Senator as an authority to sustain the invariability of the amended form which he proposes, shall I do more than say that about two years ago I was endeavoring to save the depleted treasury of the State of South Carolina from further and gross peculation and robbery, and sought by a resolution of inquiry to draw the attention of the country and of the President of the United States and his subordinates to the case so that the scheme of plunder might be arrested, if there was a disposition to do so.

In this attempt, however, I was, as usual in this body, unsuccessful, for the resolution, although it was adopted early in the month of March, 1873, and was sent to the President, was treated by him and his Secretary of War with contemptuous silence, and the wrong-doer was not only permitted to consummate his wrong, but he has been encouraged to repeat it, and to-day we find him sent to “fresh fields and pastures new” in the State of Louisiana, to repeat there the operations that made his name so notorious in the State of South Carolina. I refer to one Major Lewis Merrill, of the United States Cavalry, who has added to his notoriety by his late congenial operations in the State of Louisiana, for which he has been specially detailed by the Secretary of War with a full knowledge of the facts that preceded his conduct in South Carolina.

The amendment to the resolution originated not with me but with the Senator from New York, who now offers it in the same phrase to the present resolution. I was at that time compelled to accept it or virtually lose the possibility of having my resolution adopted. I offered it as soon as the facts were made known to me. There were but two working days left of the session, and the objection which was made upon the first day would have continued it over, and I was glad to have it accepted in any form, even with the entirely superfluous, and, as I thought then, improper addition which was put upon it. I made no objection to it. In that way alone the resolution, as amended by the Senator from New York, came before the Senate.

But. Mr. President, that is a very small matter compared to the gravity of the crisis in which I believe the people of the United States find themselves this day. If I overrate it, it is because the deep solicitude which I feel in everything touching my public duty and the welfare of my countrymen must account for the error in judgment. I do not believe that since the American colonies separated themselves from the rule of Great Britain by revolutionary action the people of this country were ever brought face to face with graver questions needing braver, calmer, more deliberate consideration than confront them to-day. It is not simply the question of the existence of that republican form of government which by the Constitution it is made the duty of the United States to guarantee to every State of this Union, and without which Louisiana stands today. It is even graver, if it be possible, more important than even that, for there are governments, of laws not republican in form, in which the objects of good government are secured and peace and safety given to the inhabitants. But the issue now to be raised between the people of the United States and those whom they have elected as their rulers is whether this Union of States shall be governed by law or by the mere personal will of the official; whether we shall have a civil government or a military dictatorship; whether we shall have a free government or a despotism. The issue is, if I mistake it not, not less grave than this. In the venerable Commonwealth of Massachusetts I find well stated the object for which, the spirit with which, these limited governments were created, and their charters reduced to writing, so that they should not depend upon the feebleness of men’s memories, but should he fixed in written characters for all time. Said the people of Massachusetts in their Declaration of Rights, in the fourth section :

The people of this Commonwealth shall have the sole and exclusive right of governing themselves as a free, sovereign, and independent State ; and they shall forever hereafter exercise and enjoy every power, jurisdiction, and right which is not or may not hereafter be by them expressly delegated to the United States of America in Congress assembled.

And in the closing section of their declaration of rights:

In the government of this Commonwealth the legislative department shall never exercise the executive and .judicial powers, or either of them; the executive shall never exercise the legislative and .judicial powers, or either of them; the, judicial shall never exercise, the legislative and executive powers, or either of them, TO THE END THAT IT MAY BE A GOVERNMENT OF LAWS, AND NOT OF MEN.

There is the soul of the declaration of rights upon which the government of the ancient Commonwealth of Massachusetts stood in 1779, and under and subject to which her people have lived to this day.

Mr. President, absolute, unlimited power is unknown to the American system of government, or to any other system of government pretending to be called free. The people of the States and the States as integral parts of the Federal Union have delegated certain enumerated powers to their rulers, and reserved all others expressly in their written charter to the States and to the people. To omit the execution of just power is clearly a breach of duty of the Executive, and to assume power not delegated is a usurpation quite as dangerous as rebellion and just as promptly to be checked.

Now, sir, in what spirit should an American Senator approach the consideration of a question like this? Should it not be gravely, moderately, restrainedly, and without excitement, discussed? How unlike should it be to the remarks which we have here printed in the records of the proceedings of this body, which fell from the honorable Senator from Indiana, [Mr. Morton,] and from his associates from Vermont and from Illinois, [Messrs. Edmunds and Logan,] in which every line seems to breathe, hatred, to blaze with excitement, to be filled with violent epithets, with general arraignment and indictment of the whole white population of a sister State, so that it seems to me their speeches must have been intended to obscure the real point at issue and to envelop the, subject in a cloud of excitement, to awaken anew the bitterness of sectional animosity; and, by sounding the trumpet of mere party, to draw their hearers away from that standard of sworn patriotic duty to support and defend the Constitution of their Government. I shall not imitate them. My sense of indignation is strong, but it is to he silenced by my sense of sorrowful apprehension of evil to my country.

Sir, in the course of the late dreadful war between the States of this Union, I heard of a widowed mother, bereft of husband, of child, of property, sitting in the midst of her desolation, with a bleeding heart, who was asked whether she did not hate those who had thus wronged her; and her answer was, “My heart is too full of sorrow, to have any room for anger.”

Now, sir, what are The facts of this case? An election on November the 3d was held in Louisiana, as in the other States. It was conducted with earnestness and some excitement, and yet peaceably—certainly orderly. The entire machinery for conducting and supervising that election was in the hands of the acting governor of the State and his political adherents. The forms of election were maintained and they were generally exercised, and the returns were wholly in the hands of Governor Kellogg, as he is called, and his adherents. He committed them to a returning board who kept them in the face of the country, under a pretense of tabulation and counting, for nearly two months, lacking I think but two days. Other States nearly five or six times as populous found their returns tabulated and correctly counted within less than a week. In most of the, great cities of the country, containing far more population than the whole State of Louisiana, forty-eight hours had not elapsed before there was a tabulation and count of the votes. But this tabulation and counting were retarded and delayed by the returning board, the appointees of Kellogg, for the foul and wicked purpose declared and proven by their opponents, forgery proven, the substitution of false returns for real returns, the arbitrary rejection of clear testimony in regard to the election; even a public holiday, the Thanksgiving Day, violated for the purpose of breaking open the envelopes and replacing the true returns by forged ones. All these things are not only alleged, but proven, and are known to the country. The delay had its object, and the object was fraud, and the fraud was perpetrated, and in every ease where fraud was perpetrated it was a fraud against the conservative party of the State and in favor of that party known as the Kellogg party. To that there is no exception; it stands the invariable rule of these fraudulent alterations.

The conservatives were vigilant, they were constant, they were courageous; but their apprehensions were but too sadly to be verified, and the overwhelming majority of the conservatives in the Legislature of the State of Louisiana was nullified, and a small majority—I believe of two votes—given to the Kellogg party in the house of representatives by the garbled, false, partial returns of this board. This was done in the presence of the whole country. Day by day the charge was made and proven. The country knew it. No one denied it. The President of the United States was advised of it; he was kept well informed of it, and his semi-official utterances, made known to the people, were that, no matter what frauds should be accomplished by this board, they should be maintained at every cost, or that “somebody should be hurt’’ in case interference was attempted with their nefarious proceedings; that is to say, if any resistance to a clear, plain wrong was made by an outraged community.

On the 4th of January the Legislature of Louisiana, under the constitution of that State, were to assemble in the Statehouse in the city of New Orleans; they were to organize their respective bodies. The constitution of the State of Louisiana provides in article 34 entitled “ Of the legislative department,” first—

That the number of representatives shall never exceed one hundred and twenty nor be less than ninety.

Art. 34. That each house of the General Assembly shall judge of the qualifications, election, and returns of its members; but a contested election shall be determined in such manner as may be prescribed by law.

Art. 35. Each house of the General Assembly may determine the rules of its proceedings, punish a member for disorderly conduct, and, with a concurrence of two-thirds, expel a member ; but not a second time, for the same offense.

Art. 37. Each house may punish by imprisonment any person not a member for disrespect and disorderly behavior in its presence, or for obstructing any of its proceedings ; such imprisonment shall not exceed ten days for any one offense.

Such is the language of the constitution of Louisiana. Now, let us consider for one instant the. value of this right given exclusively to each House to determine the rules for its own proceedings and to pass upon the elections, qualifications, and returns of its own members. Like all things that are of value, it was not reached in a day, but its path was a path of difficulty to those, who achieved if. The history of this right, this English-born right of self-government by the representatives of the people, is well related in The Law and Practice of Legislative Assemblies by Cashing, at section 146:

The present constitution of the House of Commons is, to a considerable extent, the result of a series of struggles between it, on the one hand, and the sovereign, or the lords, or both, on the other. One of the earliest of these conflicts, and one of the most interesting, is that which terminated in the establishment of the right of the Commons to be the exclusive judges of the returns, elections, and qualifications of their own members. This right, after having been claimed and exercised at one time by the king and council, at another by the House of Lords, and. again, by the lord chancellor, was declared by a resolution of the Commons, in 1624, and has ever since been admitted to belong exclusively to the house itself, as “its ancient, natural, and undoubted privilege.”

This power is so essential to the free election and independent existence of a legislative assembly that it may be regarded as a necessary incident to every body of that description which emanates directly from the people; it is also, out of abundant caution, conferred upon or guaranteed to most of the legislative assemblies of the. United States by express constitutional provisions.

In accordance with this inherent right, incidental to the very nature of the body, was the constitutional guarantee which, as the writer has said, out of plenary caution was introduced into the constitution of the Stare of Louisiana. There was a voluntary and orderly attendance of 101 or 102 elected and persons claiming to he members-elect of the house of representatives of the Legislature of the State of Louisiana on the 4th day of January instant, more than a quorum under the constitution of the, State. But under what circumstances did these representatives of the will of the people of Louisiana assemble? In the State-house, not the custom-house or any other United States building, but in the house of the State of Louisiana. And in whose hands did they find it? On the evening previous it had been garrisoned with what were called the Metropolitan police, the adherents and partisans and sole appointees of Kellogg, the acting governor. Around the house, controlling access to it upon two sides, were armed troops of the United States acting in force under the command of an officer of the United States under delegated authority from the President of the United States. The lawful citizens of the State of Louisiana were forbidden to approach their State-house. They who alone were privileged spectators were forbidden to exercise the high, the inherent, the essential privilege of witnessing the convention of their own State Legislature. There was a member of Congress, well known and esteemed by all—I refer to Mr. Potter, of New York, at present a member of the investigating committee there—who sought in vain as a private citizen of a sister State to approach and witness the form of inauguration of the assembly, and was forbidden by armed force.

I consider his rejection an outrage, and unlawful; but I consider that the poorest and the meanest citizen of Louisiana had a precedent right even over my respected friend to enter the hall and to witness the inauguration of the Legislature in whose election he had cast his vote and who were to be the. makers of laws under which he should live. But until the House committee appointed to make this investigation shall return, I will not attempt to recite any disputed or disputable fact. I shall take, facts which are admitted and established, and refer to them alone.

There was an organization of that house. There was a speaker elected and placed in his chair. There was a clerk also chosen, and this was done in the presence of a quorum of the house of representatives constitutionally convened, and by the votes of a constitutional majority of those present, quietly, regularly, and peacefully east. I will not now argue the regularity or the irregularity of the initiation of this organization. The Kellogg party may have been deceived as to their numbers, and outwitted by the defection in their own ranks, or by the superior parliamentary skill and knowledge of their opponents; the organization may have been perfectly regular, or it may have been in some degree irregular and open to criticism; but it is certain that it was quiet, that it was peaceful, and unaccompanied by any threat or act of violence on the part of any conservative member. When I say that I mean that it was unaccompanied by any show of that “domestic violence,” which is spoken of in the Constitution, which gives the President of the United States the right to interfere, and there was no pretext for the existence of anything capable of being termed “ violence” on the part of the one hundred and one members of the Legislature so convened. On the contrary, Mr. President, there was a dignity far removed from violence; there was a courage, far different from bluster, which would have become a Roman senate even in the presence of some barbarian horde. It is said that even a rude Goth at the head of his forces was impelled to yield involuntary respect to the aged and unarmed men of the Roman senate who witnessed in their placid dignity the invasion of their council chamber; but it seems that an officer of the Army of the United States is untouched by any such restraining influences, and knows no law of restraint but the will of his superior officer, no matter what may be the outrage upon the rights of his fellow-citizens, or the laws and the Constitution of his country, which he may have been ruthlessly ordered to commit.

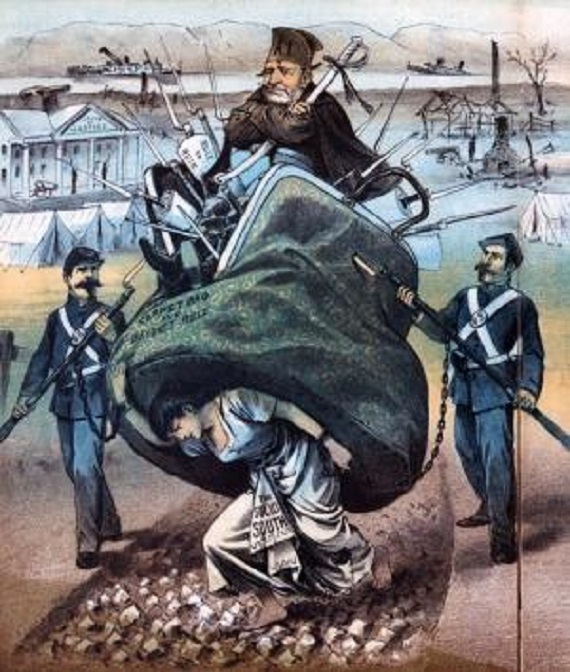

The house of representatives of Louisiana was on the 4th of this present month purged of five members who were in their official seats, quietly and peaceably filling their places in that body, having been admitted and sworn into office by the only competent body to admit them or pass upon their qualifications. They were purged just as in 1648 one Colonel Pride, with his two regiments, purged the house of Parliament at the order of a Cromwell: seized forty-one members, displaced them by force, excluded one hundred and sixty others, and thus he constituted that fag-end of a government that has come down hissed by posterity as the “rump” of a parliament, and which lived its wretched and disgraceful career five short years, until the hand of the master that had constituted it drove it with shame from the place where his power alone had placed it. Sir, does not history repeat itself, and will men be forever deaf to its lessons until they burn themselves in by painful experience?

Mr. President, I ask the Senate, I ask the American people, had President Grant the legal warrant for interference by troops at that time, in that manner, at that place? Had Governor Kellogg the power himself to do it? Had he the lawful power to call upon the President or any other person to interfere as was done on that day? Where is the law, where is the constitutional provision from which such right can be implied, however remotely or indirectly? There has been none yet cited, and I make bold here to-day to say that this debate will begin and it will close, and there will be no lawyer, as I believe, of this body who will be able to produce the statute or even attempt to twist or force the construction of words that will give any warrant for this act.

There stands the constitution of the State of Louisiana, the provisions of which I have read. There, stands the Constitution of the United States, containing its enumerated and delegated powers to the President as to all other departments of this Government. Where do we see them now? Overthrown and cast down by the furious lawlessness, by the unlawful ambition, of these, two officials whom I have named, the creature and the creator. Look at it, Senators! Look at it, people of the United States! Contemplate the picture of that dispersed Assembly; read the protest of the peaceable and orderly men ejected by brute force from their lawful places in that Assembly, and then say whether party passion or sectional prejudice can constrain you to approve it, or prevent you from grave and deliberate condemnation of the act, and of those who have committed it.

But, Mr. President, such conduct is, I am sorry to say, not now in Louisiana. It is but a leaf out of the book of the sad story of that State. Two years ago it was under pretended forms of law, that only made the fact more loathsome, by mingling more fraud with force. The act to-day is more bare-faced, and in that I think there may he some security to my fellow-countrymen.

I will take leave, not in egotism but in justification of what I say to-day to read same remarks which I made in the Senate on the 27th of February, 1873, at the hour of six o’clock in the morning, when I and others had been kept here in weary and fruitless debate upon some bill relating to the State of Louisiana unauthorized, as I believe utterly unauthorized, by the Federal Constitution. I said then:

I believe it is never wise to blink the truth. I believe it is never wise in governing a people in any way to deceive them, or to rule them by false promises. And here I state to the Senate and the country that I believe these governments ‘’so called ” in the Southern States are but thin veils for actual military power in the hands of the Federal Administration. Those governments are permitted to exist so long as they please “the powers that be.” So long as they pronounce the shibboleth of your party, so long and no longer those who represent the governments will be protected, but it is intended to overshadow them from time to time by the hand of Federal power, so that they may be taught that unless they do conduct themselves according to the will of their real masters, not even the forms of republican government shall exist, It matters not whether the end is reached by Durell and his s pretended “judicial ” orders, or Casey with his Gatlin guns or revenue-cutters, or Attorney-General Williams with his ‘”‘fusion ” suggestions, or swarms of United States marshals and their deputies to enforce congressional election laws—all are part and parcel of the scheme and system of that coercive power which is the real government of this country.

Sir, if the President of the United States shall proclaim martial law in Louisiana, if he shall take possession of that State, lie will only be doing openly what his party in fact have been doing for the last six or seven years under the thin veil and flimsy disguise of legal forms. There has not been a time when troops have not either actually gone there or have been threatened to be. sent there. No one can doubt that Judge Durell would never have dared to issue this order, nor would any one have thought of obeying it, if there had not been an intimation to him that the power of the Federal Army would back him up and would sustain the faction that he was creating under the name of a government. I do not doubt it. I do not think the people of this country can doubt it; at any rate, I say herein my place to them I believe it to be true, and I think the facts warrant this belief.

Therefore, sir, believing at any time that I would rather know my fate, and I trust I will never be afraid to look my fate in the face. I do feel that our Government is passing away from us because we are losing the disposition and the means of enforcing those limitations upon the powers of those whom rule us, and they are disregarding them. That which is the law for Louisiana to-day may be made the law for Pennsylvania or New York tomorrow. It has been threatened in New York ; it has been carried almost to the same- point in New York; her peaceful streets have been tilled with Federal troops on the occasion of popular election; her waters and her docks have held armed vessels ready to hail destruction upon her citizens and their property. Those things have, been witnessed by the American people, but their meaning seems to have been but faintly understood; and now I would say to the people of every other State. “Read in the fate of Louisiana today what well may be your own when the necessities of party shall call upon those, in power to make it so.”

I know that I say this at the commencement of a new lease of power of the republican party, when we are to have four more years of government probably by the same Executive, possibly by the same Congress as heretofore; and yet, nevertheless, the time must come when the people of this country shall again express their will, and all that I can do is to tell them the truth as I see it, and then if it be my fate to stand in the minority, that will not the least silence my voice; that will not the least change my ardent aspirations to serve my fellow men, and I shall warn them, as I warn them now, of the dangers I apprehend, and indicate the proper modes of meeting them.

Such, sir, were my views expressed here in open debate, nearly two years ago. Again, when this subject was up on the 20th of April, 1874, 1 stated the fact that—

Under the thin veil of a pretended republican form of government, the real govern meat of Louisiana to-day is military force. It is a sham to call it anything else. You lift the gown of the judge, and you find the saber of the dragoon; you enter the executive chamber, and the power there is the power of the sword and not of the law. The government of Louisiana to-day is nothing but military power, protecting dishonest men who wear the sham robes of State office.

Mr. President, has this policy on the part of the President been changed? Heading by the events of to-day this ineffectual debate of mine nearly two years old, who shall challenge the truth of those utterances? They were sincerely made; they have been confirmed by time, the irrefutable register of truth. What has been the policy of the President of the United States? Has it been moderated or modified? Nay, sir, it has only been doggedly intensified. There is not in that State one ease of abuse of power, of peculation, robbery, and filthy dishonesty, with which the history of its government is tilled in the last two years, in which his displeasure has ever been signified by the removal of an improper official, not one word of rebuke. On the contrary, there has been personal and official encouragement of men who stand before the nation branded as dishonest and unworthy, and whom no man would trust with his private affairs or give power to in matters affecting himself in any way.

In the midst of this excitement, in the midst of this blow at the very heart of popular government, who has he selected to preside over the affairs of that State? Lieutenant-General Philip Sheridan, sent by him to New Orleans secretly, not by public order known to the people. He is sent down to dragoon the people of Louisiana into slavish, fearful, cringing, un-American obedience to his will and pleasure. He arrives then only three days before the assembling of the Legislature. He sees none of those who have the welfare of the community at heart. From Kellogg and his adherents, the men who have brought this trouble and sorrow upon the State by their own corrupt and selfish ambition, he takes his account. They inform him, they inspire him, and from the recesses of his pocket he suddenly produces the authority and “assumes the command of that military district,” over which there was already a competent commander regularly and publicly assigned. Instantly, without other public order, that commander is superseded, other officers both higher and lower in rank than General Sheridan are passed by, and he is personally selected to undertake the task of unlawful interference with the free government of a sovereign State of this Union.

Now, it is not my purpose in any degree to detract from whatever of renown may have rested upon the brow of this officer. I would be incompetent to criticize his military career, and that is all I believe that he has. It is a career of force, a career of vigor, a career of rough war of which I know but little, and therefore am incompetent to criticize him as to that respect, But, sir, I also know that he is an officer of the Army of the United States, that he is fed and clothed by the people of the United States, and that he is the servant of those people, and not in any just sense their master; that he received the military education that has enabled him to become so eminent at the national academy and at public cost. The Constitution of the United States is still a text-book of that institution. It was a text-book when this officer received his graduation; and yet it seems to me that while he must have read it while he must have known that his commission as an Army officer took its roots in the principles of civil liberty which that Constitution was intended to secure, yet he has forgotten almost its first and most necessary instructions. Sir, has he not forgotten that, “a well-regulated militia being necessary to the security of a free State, the light of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed?” Has he not forgotten that “the right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects against unreasonable searches and seizures shall not be violated? That “ no person shall be held to answer for a capital or otherwise infamous crime unless on a presentment or indictment of a grand jury, except in eases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the militia when in actual service in time of war or public danger?” Nor that any person shall be “deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process of law?’’ That “in all criminal prosecutions the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial by an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by law, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation, to be confronted with the witnesses against him, to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the assistance of counsel for his defense?”

Sir, if these things were read by that officer, surely he must have forgotten them, or else has the more guilty audacity to ride roughshod over them. If he has forgotten, let him now be taught anew. Let us see who is the stronger. The issue cannot come too soon. If this cavalry officer, with whatever renown he may have gained with his bloody sword, shall be stronger than these guarantees of personal liberty which we supposed were secured to us, let us know it now. We cannot have the issue raised too soon or too distinctly decided.

Now, sir, I ask the Senate and the country to listen to the tone, of this officer and see, when yon have read his dispatches to the Administration here, who shall say he is even fit to breathe the air of a republican government. I believe this officer reached New Orleans about, the 1st of January, and on the 4th of January he telegraphed to the Secretary of War Hon. W. W. Belknap, as follows:

HEADQUARTERS MILITARY DIVISION OF MISSOURI,

New Orleans, January 4. Hon. W. W. Belknap,

Secretary of War, Washington D.C.

It is with deep regret that I have to announce to you the existence in this State of a spirit of defiance to all lawful authority and an insecurity of life which is hardly realized by the General Government or country at large. The lives of citizens have become, so jeopardized that unless something is done to give protection to the people all security usually afforded by law will be overridden. Defiance to laws and murder of individuals seem to be looked upon by the community here from a stand point which gives impunity to all who choose to indulge in either; and the civil government appears powerless to punish or even arrest. I have to-night assumed control over the Department of the Gulf.

P. H. SHERIDAN, Lieutenant-General.

“Assumed control over the Department of the Gulf!” Here is then from the hand of this mere soldier, military in instinct, and in education, and ignorant of civil right or law, the cool complacence of ignorance, that he could do that of which even the great mind of the most philosophic statesman and lawyer of modern times declared himself incapable, Burke declared he could not draw an indictment against a whole people; but it seems that—

Fools rush in where angels fear to tread.

Mr. Sheridan can indict an entire community and declare this wholesale destruction of their moral character upon three nights’ acquaintance in one city of a large State. Mr. President, there have been replies to this, made upon the instant these telegrams -were published.

At a meeting of the Merchants’ Exchange, largely attended, the following series of resolutions were unanimously adopted :

Be it resolved, That we condemn as a positive untruth and as a libel upon the community the statement of General Sheridan, contained in the above; that we deny herewith that the spirit of defiance against lawful authority exists and that the lives of citizens have become jeopardized thereby.

Resolved, That we emphatically condemn, as law-abiding citizens, and do most solemnly and earnestly protest against, the military interference with and the disorganization of the Legislature of Louisiana, which was duly elected by ourselves and the citizens of the State.

The board of underwriters met and passed similar resolutions, denouncing as utterly untrue and unwarranted these assertions of the Lieutenant-General. The Cotton Exchange, on the same day, had a full meeting, and adopted the following unanimously:

Whereas General P. H. Sheridan, commanding the Military Division of Missouri, has seen fit to address to the honorable Secretary of War a letter, dated January 4, and published in our papers of this date, in which he has given utterance to statements reflecting upon the people of this State, and particularly of such as reside in this city, singularly at variance with the condition of things now and heretofore existing in this city and State, and well calculated not only to detract from our good name as law-loving and law-abiding citizens, but also to seriously injure the commercial interests of our city, the Cotton Exchange, an organization totally disconnected from political affairs, and instituted solely for the promotion of commercial interests, feels called upon to enter a solemn protest against the allegations contained in said letter.

The members of this exchange give solemn assurance to the people of the United States and to the friends of truth and justice wherever found, that the allegations of General Sheridan are not only false, in point of fact, but evince the spirit of a mere partisan rather than the nobility of a soul which should characterize the utterances of an officer commanding the army of a great nation. It is painfully evident that, coming among us an almost entire stranger, General Sheridan has limited his inquiries into the condition of affairs here to those whose interests it is not only to falsify facts but to promote that spirit of lawlessness with which we are falsely charged. It would not indeed be a matter of surprise if crimes in our midst were more frequent, when it is borne in mind that the police force, for the maintenance of which we are heavily taxed, is now, and has been, diverted from its legitimate, duties to such an extent that large districts of our city are entirely without protection, and many of our citizens are compelled to employ private watch-men for protection against thieves and burglars.

Then came an address from the committee of seventy citizens of New Orleans, gentlemen of standing and character, the meanest man among them the peer in all respects of this officer of the United States Army who has slandered them, in which they protest against his calumnious statements, and call upon the people of their State to exercise more of heroism and patience and forbearance, which will arouse the sympathies of the entire country in their behalf; and God grant it may.

Then comes an appeal of the clergy of New Orleans to the American people.

To the American people:

Whereas General Sheridan, now in command of the Division of the Missouri, under the date of the 4th instant, has addressed a communication to Hon. W. W. Belknap, Secretary of War, in which he represents the people of Louisiana at large, as breathing vengeance to all lawful authority and approving of murders and crimes: We, the undersigned, believe it our duty to proclaim to the whole American people that these charges are unmerited, unfounded, and erroneous, and can have no other effect than that of serving the interests of corrupt politicians, who are at this moment making the most extreme efforts to perpetuate their power over the State of Louisiana.

N. J. PERCHE

Archbishop of New Orleans.

J. P. B. WILMER

Bishop of Louisiana.

JAMES K. GUTHERIM,

Pastor Temple of Sinai.

J. C. KEENER,

Bishop M. E. Church South.

C. DOLL,

Rector St. Joseph’s Church. (And many others.)

Then again in to-day’s paper there is a protest from other divines, the Bishop of Little Lock and others. In another dispatch of General Sheridan, which I have not yet read, he goes farther and arraigns not only the people of New Orleans, Louisiana, but the entire communities of three States, in none of which does it appear he has been except for the period of three days at the city of New Orleans.

Let me now read further. On the 5th of January he telegraphs the Secretary of War at Washington:

HEADQUARTERS OF THE MILITARY DIVISION OF MISSOURI

New Orleans, Louisiana, January 5, 1875. Hon. W. W. BELKNAP,

Secretary of War, Washington, D. C. :

I think the terrorism now existing in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Arkansas could he entirely removed and confidence and fair dealing established by the arrest and trial of the ringleaders of the armed White Leagues. If Congress would pass a bill declaring them banditti, they could be tried by a military commission. This banditti, who murdered men here on the 14th of last September, also more recently at Vicksburgb, Mississippi, should, in justice to law and order and the peace and prosperity of this southern part of the country, be punished. It is possible that if the President would issue a proclamation declaring them banditti, no further action need be taken except that which would devolve upon me.

P. H. SHERIDAN, Lieutenant-General United States Army.

Ah, Mr. President, if there was the tone that under other administrations animated the Executive of this country, he would never sign his name again as Lieutenant-General of the United States Army. Is this the language of an American officer toward his fellow-countrymen? Why, sir, if he were in a hostile country among the sick and wretched Piegan Indians, had he been in the service of Mexico, there could not have been a more ruthless, a darker, or more bloody threat than is contained in the closing lines of this dispatch to the Secretary of War. This is language relating to the citizens of three States of this Union. Is it the language that is due from an officer of the Army of the United States, wearing that honorable uniform, the protector, the guard, the glory of his people, without distinction of party; or is it not the language of some captain of a band of janizaries, asking orders from an oriental despot in regard to his ruthless extermination of those whom he may deem the foes of power? This man, educated with one of his text-books the Constitution of his country, asks that Congress shall pass an ex post facto law, making that a crime which was not a crime at the time of the commission of the alleged offense, and creating new punishments to make the penalty still more severe. He asks for military commissions, in these times of peace, to try men neither in the land nor naval service of the United States. He asks for drum-head court-martials to try citizens over whom there is no pretense that the authority of the Army or of the Navy is extended. What is the dark and bloody threat at the close of his dispatch for Senators? What did he mean when he asked the President to issue a proclamation declaring these citizens banditti, and that then no further action need be taken except that which would devolve upon him?

I confess to you as I read this dispatch my blood curdled in my veins. If it had been sent in the midst of strife by a man heated by the excitement of combat, there might have been palliation for it, because a cooling time would have, come when his better reason would operate, when “Philip sober” would have answered this “Philip drunk.” But this dispatch was penned in safety; it was penned in quiet; it was penned where there was nothing that threatened him, and without anything to cause him excitement except the apprehended loss of political power to the chief whom he was sent there to represent.

What character does this officer seek to assume ? There, was Tristan l’Hermite, the provost-marshal of the royal household, whom the genius of Scott has painted until he is familiar in every household. It seems to me that this officer has modeled himself much upon the morals and conduct of this hangman of royalty of days gone by.

Sir, I say that in a proper condition of sentiment with those in power he would not have been suffered to remain for five minutes in command at New Orleans. He has no one quality that fits him properly for the duties of command there now. His first requisite should be good-will and kindness to the people, strict impartiality; no threats of force, careful obedience to civil rule. This was the example he should have set as a high official, honored by his country, and invested with high discretionary powers; and, as this example does not seem to originate with him, I want it now taught him, and taught so that not alone he will not forget, but that every other officer of the Army and Navy of the United States will learn and know that it is in the affections, in the respect of their fellow-countrymen, and not in their fears, that they are to find their place of honor and of safety.

Sir, I said he has cruelly maligned these populations among whom he has gone, and I have allowed them in their own way to answer him, not beginning to recite the numerous protests that have followed his false and calumnious charges against them. Sir, it is perfectly shocking, and I think a civilized world everywhere must be deeply shocked when such dispatches are read. We have talked about the Russian rule in Poland and have held it up as an abhorrent example of cruelty; but what dispatch ever sent to a Russian Czar exceeded in remorseless savagery the closing lines of the dispatch of General Sheridan on the 5th of January to Belknap, Secretary of War? I wish it ended there, I wish it ended with him; but alas! alas! here we find on the 7th of January the Secretary of War answering in the following phrase:

Your telegrams all received. The President and all of us have full confidence and thoroughly approve your course.

I know not how fitly to designate such a communication, except to say that every expression of disgust, of horror, of antagonism that I have expressed toward the action of General Sheridan in his dispatches is rather increased toward those who could pen or concur in such an answer as that. The American people must answer it. They must answer it from their hearts, and I believe there is after all in the human heart such a response to kindness, such a natural love of justice, that they will repudiate Mr. Belknap “ and all of us ” to whom he so loosely and generally refers, should they undertake to endorse the action of General Sheridan in New Orleans and his dispatches to the Department of War.

Mr. President, in 1866 the Supreme Court of the United States found it necessary to pass upon the questions now raised by General Sheridan and proposed to be applied, not one year after the close of an excited, a dreadful, and extensive civil war, but ten long years after the war has gone by and the hearts and hands of the American people have come once more together—are proposed to be applied by him not even as a law, but under the simple, arbitrary fiat of the President of the United States. Said this court in considering the ease of Milligan, who had been tried, who had been condemned and all but executed by a military commission in the State of Indiana:

The controlling question in the case is this: Upon the facts stated in Milligan’s petition and the exhibits filed, had the military commission mentioned power in its jurisdiction legally to try and sentence him? Milligan, not a resident of one of the rebellious States or a prisoner of war, but a citizen of Indiana for twenty years past, and never in the military or naval service, is, while at his home, arrested by the military power of the United States, imprisoned, and, on certain criminal charges preferred against him, tried, convicted, and sentenced to be hanged by a military commission organized under the direction of the military commander the military district of Indiana. Had this tribunal the legal power and authority to try and punish this man?

No graver question was ever considered by this court, nor one which more nearly concerns the rights of the whole people, for it is the birthright of every American citizen when charged with crime to be tried and punished according to law. The power of punishment is alone through the means which the laws have provided for that purpose; and if they are ineffectual, there is an immunity from punishment, no matter how great an offender the individual may be or how much his crimes may have shocked the sense of justice of the country or endangered its safety. By the protection of the law human rights are secured; withdraw that protection, and they are at the mercy of wicked rulers or the clamor of an excited people. If there was law to justify this military trial, it is not our province to interfere: if there was not, it is our duty to declare the nullity of the whole proceedings. The decision of this question docs not depend on argument or judicial precedents, numerous and highly illustrative as they are. These precedents inform us of the extent of the struggle to preserve liberty and to relieve those in civil life from military trials. The founders of our government were familiar with the history of that struggle, and secured in a written Constitution every right which the people had wrested from power during a contest of ages. By that Constitution and the laws authorized by it this question must be determined. The provisions of that instrument on the administration of criminal justice are too plain and direct to leave room for misconstruction or doubt of their true meaning. Those applicable to this case are found in that clause of the original Constitution which says “that the trial of all crimes, except in case of impeachment, shall be by jury;” and in the fourth, fifth, and sixth articles of the amendments. The fourth proclaims the right to be secure in person and effects against unreasonable search and seizure, and directs that a judicial warrant shall not issue “without proof of probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation.” The fifth declares “that no person shall be held to answer for a capital or otherwise infamous crime unless on presentment by a grand jury, except, in cases arising in the land or naval forces or in the militia when in actual service, in time of war or public danger, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process of law.”

The court proceed to recite the amendments, which I have read in full before, to secure the personal liberty of the citizen:

These securities for personal liberty thus embodied were such as wisdom and experience have demonstrated to be necessary for the protection of those accused of crime. And so strong was the sense of the country of their importance, and so jealous were the people that these rights, highly prized, might be denied them by implication, that when the original Constitution was proposed for adoption it encountered severe opposition; and but for the belief that it would be so amended as to embrace them, it would never have been ratified.

Time has proven the discernment of our ancestors; for even these provisions, expressed in such plain English words that it would seem the ingenuity of man could not evade them, are now, after the lapse of more than seventy years, sought to be avoided. Those great and good men foresaw that troublous times would arise, when rulers and people would become restive, under restraint, and seek by sharp and decisive measures to accomplish ends deemed just and proper, and that the principles of constitutional liberty would be in peril, unless established by irrepealable law. The history of the world had taught them that what was done in the past might be attempted in the future.

No doctrine involving more pernicious consequences was ever invented by the wit of man than that any of its provisions can be suspended during any of the great exigencies of government. Such a doctrine leads directly to anarchy or despotism; but the theory of necessity on which it is based is false; for the Government, within the Constitution, has all the powers granted to it which are necessary to preserve its existence, as has been happily proved by the result of the great effort to throw off its just authority.

On the following page—

It is claimed that martial law covers with its broad mantle the proceedings of this military commission.

That is what this officer desires the President of the United States to proclaim, thinking that a proclamation by the President will be a carte blanche to him to steep his hands in the blood of his fellow citizens in that city.

It is claimed that martial law covers with its broad mantle the proceedings of this military commission. The proposition is this: That in a time of war the commander of an armed force, (if in his opinion the exigencies of the country demand it, and of which he is to judge,) has the power, within the lines of his military district, to suspend all civil rights and their remedies, and subject citizens as well as soldiers to the rule of his will; and in the exercise of his lawful authority cannot be restrained, except by his superior officer or the President of the United States.

If this position is sound to the extent claimed, then, when war exists, foreign or domestic, and the country is subdivided into military departments for mere convenience, the commander of one of them can, if he chooses, within his limits, on the idea of necessity, with the approval of the Executive, substitute military force for and to the exclusion of the laws, and punish all persons as he thinks right and proper, without fixed or certain rules.

The statement of this proposition shows its importance; for if true, republican government is a failure, and there is an end of liberty regulated by law. (4 Wallace’s Reports.)

I will not apologize for the length of the extract I have read because these truths are of cardinal importance at this crisis of affairs, and, being gravely enunciated by this high tribunal, should have influence upon every man within this Chamber, as well as every citizen in the United States.

It was my duty three years ago as a member of a committee of this body, to investigate the condition of affairs in the State of North Carolina, to spend with my associates two or three months in taking testimony, and then we submitted reports upon it. Unable to concur in the report of the majority, the minority, consisting of myself and one of the most gallant soldiers of the late war, (Senator F. P. Blair, of Missouri,) presented their views. At the time this minority report was made we closed it with a notation from an eminent statesman, to which exception was taken under a misunderstanding by my friend from Pennsylvania, [Mr. Scott,] and I remember his reading it as though under an idea that it was meant to be descriptive of himself in any degree. The proposition was abstract and most true, in regard to the effect upon men’s character and nature of continued acts of violence and oppression. I read this extract from our former report, because its truth has been vindicated by what has since occurred, and is vindicated still more to-day by the example which this correspondence of a lieutenant-general of the Army and the War Department has afforded to us and to the American people. We there stated in regard to the case of North Carolina:

This is the truth in a nutshell; that Holden and his official supporters have failed to maintain themselves by any means, foul as well as fair, in their State. They have appealed to popular election, and have been rejected with something near unanimity by every tax payer in the State; and now Congress is asked to step in and force North Carolina down again under the feet of her radical masters; and we fear that Congress will attempt to do this unwise and wicked thing. Will the people of the North (free as yet) see this thing done and sustain its promoters ? We hope not; we pray not. When will the men now in power learn the truth of what the great statesman of the last century said so wisely and well, when similar attempts were made to govern British India?

“It is the nature of tyranny and rapacity never to learn moderation from the ill success of first oppressions. On the contrary, all men thinking highly of the methods dictated by their nature attribute the frustration of their desires to the want of sufficient rigor. Then they redouble the efforts of their impotent cruelty, which producing, as they must produce, new disappointments, they grow irritated against the objects of their rapacity; and their rage, fury, and malice (implacable because unprovoked) recruiting and re-enforcing their avarice, their vices are no longer human. From cruel men they are transformed into savage beasts, with no other vestiges of reason left but what serves to furnish the inventions and refinements of ferocious subtlety for purposes of which beasts are incapable and at which fiends would blush.’’

Sir, is it not true that the legislation of Congress was cruel and severe; and in what did it result, and what have we to-day in Louisiana? The Senator from Indiana [Mr. Morton] to-day has rather improved upon his well-known powers of denunciation in regard to those communities. There is even more often repeated the savage and relentless epithets of murder, and of blood and of assassins with which he has sought to stain the names of those people. He has progressed and intensified it; and no such ruthless instrument has apparently yet responded as he who has responded last. General Sheridan is more cruel than those who have preceded him; he is more ruthless, and he holds out to his fellow-countrymen murderous threats which are disgraceful to the cloth he wears and to the country of which he is a citizen.

Mr. President, I desire to say to the people of this country and to the Senate that the proposition is now here presented for the first time that the President of the United States can, of his own motion and in his own discretion, adjudge the fact that such “ domestic violence’’ at any time exists within a State as to authorize him, either by his powers as President or by power delegated to him by the governor of that State, to interfere in the organization of a State Legislature. This is the proposition. The power is as secure under the constitution of the State to the Legislature to judge of the qualifications, returns, and election of its own members as it is to either House of the Congress of the United States. One is as equally essential to the continuance of our form of government as the other. The Legislature of Louisiana have as much rightful power to pass upon the qualifications of members of this body or of the other House of Congress as have both these Houses of Congress to pass upon the qualifications of members of that Legislature. The same frame of words is used to secure the separate rights and powers of each. If one cannot protect itself by the respect due to established law, neither can the other. If lawless physical force shall be permitted to overthrow the rights of one, it can also overthrow the other. In either case it is a question of degree alone.

I do not embark upon any sea of defense of the southern people against these widespread vague calumnies. I only wish to bring the American people to consider this point: If you admit such a power as this to be exercised in the discretion of the President, then pursue it plainly to its ultimate and logical results. It is Louisiana to-day: it may be New York tomorrow; it may be Massachusetts the day following; it may be in the Congress of the United States on the 4th day of March next. Why did General Grant send his troops and exercise their lawless power within the Legislature of Louisiana by compelling members as old, as grave, as learned, as respectable as him who occupies the chair of the Senate to-day to leave their places? Pretense of “ domestic violence ” by five elderly and respectable gentlemen, unarmed, in the midst of Kellogg’s myrmidons and a brigade of United States troops! It is a farce to say that those five men were creating “domestic violence ” which authorized armed intervention by the President. Did the constitution of Louisiana give Kellogg a right to interfere in the organization of the Legislature? Just such as it gave to President Grant, and no more. Either was a lawless intruder, and nothing but the helplessness of the Legislature prevented them from lawfully imprisoning every officer and soldier who interfered with their proceedings. It was not the absence of right, but the sheer want of physical power to enforce it.

Mr. President, if the President can do this with two regiments of troops, then a single brigade will suffice to accomplish the same thing in this Capitol on the 4th of next March. There is no physical power in Congress successfully to resist such physical force. There are some seventy-four members in this body, and less than three hundred members of the other house. The same proportion of troops would be required, and a single brigade can take charge of this Capitol, shut off the entrance of the people, let in those whom they see fit, and give certificates to the Clerk of the present House of Representatives, who shall exclude all others. All that can be done, provided the physical power of the Congress of the United States is all that stands in the way. But, Mr. President, that is not all that stands in the way. The American people stand in the way, and so they should, and so I believe they will overwhelmingly, when they come to comprehend this case of Louisiana, freed from the clamor of partisans, stand in the way of this outrage upon the rights of a single State, in which yon have but to change the name and you can apply the doctrine to every one of the remaining thirty-six.

We have had the question here before now as to whether, even when we come to pass upon election returns and qualifications of members of this body, we can undertake to determine the qualifications of the constituent bodies which elected them. It has always been denied; and yet here we have decided, even where the Constitution gives to each House of Congress the right to examine into those returns, that you must pause upon the threshold of a State Legislature and not venture to pursue your inquiry as to the election and qualifications of its members. The violation of principles, in my opinion, will always return to plague those who invented it; and I here to-day in my place most solemnly warn my countrymen against permitting such a precedent as this to escape without instant and most emphatic condemnation of the act, and of all who have been concerned in its perpetration.

The Supreme Court of the United States in 1870 delivered an opinion which led them to consider the relation of the States and the General Government, with a single dissent, and that a partial one, being rather to the application than to the doctrine enunciated. It will not fall with less weight upon the ear of the American people when I say that it was from the lips of the late Judge Nelson, of New York—clarion et venerabile nomen—that these views of the relations of State and Federal Government came.

The court say:

That the sovereign powers vested in the State governments by their respective constitutions remained unaltered and unimpaired, except so far as they were granted to the Government of the United States. That the intention of the framers of the Constitution in this respect might not be misunderstood, this rule of interpretation is expressly declared in the tenth article of the amendments, namely: “The powers not delegated to the United States are reserved to the States respectively or to the people.’’ The Government of the United States, therefore, can claim no powers which are not granted to it by the Constitution, and the powers actually granted must be such as are expressly given or given by necessary implication.

The General Government and the States, although both exist within the same territorial limits, are separate and distinct sovereignties, acting separately and independently of each other within their respective spheres. The former in its appropriate sphere is supreme; but the States, within the limits of their powers not granted, or in the language of the tenth amendment “reserved,” are as independent of the General Government as that Government within its sphere is independent of the States.

Such being the separate and independent condition of the States in our complex system, as recognized by the Constitution, and the existence of which is so indispensable, that without them the General Government itself would disappear from the family of nations, it would seem to follow, as a reasonable, if not a necessary consequence, that the means and instrumentalities employed for carrying on the operations of their governments, for preserving their existence, and fulfilling the high and responsible duties assigned to them in the Constitution, should be left free and unimpaired, should not be liable, to be crippled, much less defeated by the power of another government, which power acknowledges no limits but the will of the legislative body.

Without this bower, and the exercise of it, we risk nothing in saying that no one of the States under the form of government guaranteed by the Constitution could long preserve its existence. A despotic government might. (11 Wallace’s Report, 124-126).

So, sir, we have here from the calm, serene height of judicial eminence such a description and history of the true relations of the States to the General Government that we can more clearly appreciate the utter ruin and confusion which would come from admitting the rightful attempt of such power as has been attempted by the President of the United States within the State of Louisiana. This interference at all, under the guise of “recognition,” has proceeded to a most dangerous and threatening extent. In 1844, when this doctrine was first broached in the ease of the State of Rhode Island, the power was there adjudged to be vested in the political branch of the Government, and not to the judicial, to decide as to the rightfulness of two governments claiming each to represent a State. A message was sent by the then President of the United States which, it strikes me, ought to avail much with those who desire to come at a clear and proper understanding of our present crisis.

I resist—

Said he—

the idea that it falls within the executive competency to decide in controversies of the nature of that which existed in Rhode Island, on which side is the majority of the people, or as to the extent of the rights of a mere numerical majority. For the Executive to assume such a power would lie to assume a power of the most dangerous character. Under such assumptions the States of this Union would have no security for peace or tranquillity, but might be converted into the mere instruments of Executive will. Actuated by selfish purposes, he might become the great agitator, fomenting assaults upon the State constitutions, and declaring the majority of to-day to be the minority of to-morrow; and the minority, in its turn, the majority, before whose decrees the established order of things in the State should be subverted. Revolution, civil commotion, and bloodshed would be the inevitable consequences. The provision in the Constitution intended for the security of the States would thus be turned into the instrument of their destruction. The President would become in fact the great constitution maker for the States, and all power would be vested in his hands.—House Journal, First Session Twenty-eighth Congress, pages 765, 766.

This is a fair picture of what would necessarily be the result if such power is admitted to exist lawfully in the hands of the President as he and his subordinates have attempted to exercise in Louisiana.

Sir, now presented, feebly I admit, but presented I believe fairly by me to the judgment of this Senate and to the American people. They can answer now whether the qualifications of members who are to be summoned either to a State Legislature or to a Federal Legislature—for both are governed by the same language; the one found in the Federal Constitution, the other found in the constitutions of the States—shall be passed upon by the Executive. The power given in Louisiana to her Legislature to judge each house of the election, return, and qualification of its members is just as sacred, just as clearly given as that which enables the members of this body or the other House of Congress to judge of the qualifications of its membership. If language, if clear constitutional law and provisions cannot have the effect to protect one, then they will not have the effect to protect the other, and it seems to me to be a mere feeling of the popular pulse on this subject to see how far this attempt of power can he extended without resistance. If it shall be accepted, if my fellow-countrymen shall forget what constitutes liberty and the vigilance necessary to protect that, which was gained by so much toil and suffering by their ancestors, and if they shall disregard it in respect of a portion of their fellow-countrymen and one of the members of this Union of States, then depend upon it they will shortly be called upon to meet it on a broader scale, protected by no other right than the nominal sacredness of law as superior to official will.

I said, sir, that I was glad that this last act in Louisiana was but a barefaced exercise of brute force, unaccompanied by any veil or cover of false decision by corrupt courts. I believe that, in what I must think the utterly disingenuous statement of the President in 1872 that he meant simply to obey the orders of the courts, there was the suggestion that he was acting in subordination of the military to the civil power, that he was bowing his head, backed by the Army and Navy, before the decree of some feeble but just-minded magistrate; and there, was in that something that recommended his action to that portion of the American people who would not or who could not comprehend the real history of his action. But that poor veil is now fortunately thrown aside. All men agree that Durell’s action in 1872 was fraudulent and absolutely void. He himself has resigned, hoping to escape trial, thus confessing his guilt in open court; and no man in this body, however heated by partisanship, has ventured to say that there was justification of law for the orders of Judge Durell by which a Legislature in 1873 was dispossessed of its rightful power, a State-house seized and garrisoned with United States troops, a defeated minority placed in legislative power, and the usurper, Kellogg, tossed into the governor’s chair and kept there by the armed forces of the United States.

But now there is no Durell, then are no alleged “orders of a court ” to be respected, there is no pretense of bowing the power of the military before the civil law; but it is the mailed hand of the soldier that stands to-day the sole emblem of power in the State of Louisiana, plainly, unmistakably. I do not propose to go over the tangled story of falsehood, fraud, and wrong which marked the Louisiana ease from 1872 to this day; but to-day my countrymen cannot doubt, for “ he that runs may read ’’ the history of what is to-day, and of what I fear, if it is not checked, it will be from this time on.

Sir, this story of Louisiana and her wrongs is as old as the story of the human heart. If men are not comfortable and are not happy, they will be turbulent and they will be discontented. And what people, I ask, ever were happy under the rule of strangers and of aliens? It need not be that the stranger or the alien is necessarily corrupt, wicked, or unjust, Grant even that he were not: he is not their choice; he is not of their kith and their kin; he has not that blood which is thicker than water, and which we all feel binds us to those among whom we were born and have lived; a feeling that causes even the quiet earth itself to seem sweeter if it is our birth-place, and is implanted in our very instincts. And are human laws to be made, without reference, to human instincts! Are you to eviscerate from the men, women, and children you propose to govern their natures and those habits which have become nature? And if you do, can you expect the natural effects not to follow? You disregard their happiness. Can they consider yours? If you render them unhappy and insecure in regard to themselves and to their affairs, will they care to promote your happiness and your security ? But no, sir; the rule is a plain and clear one: and would to God this Congress for an instant would listen to the common dictate of humanity and respond to it. Give these people a government they can love; let men rule over them whom they can respect: but do not give them these shams of free government, and not expect the results of tyranny to flow and form it. It will not work, gentlemen. The machinery of this country’s government was not intended for a despotism, and you cannot reach its results without radically changing that machinery, and at last in Louisiana it has been openly sought to be radically changed.

Where the people of the Southern States have been permitted to elect their own rulers and make laws which produce content, peace and quiet have followed, and this you all know, because there is not a man in this body or out of it who cannot with perfect safety and welcome go to any part of the Southern States, if he only goes there as a friend and well-wisher of the people; and if he be not, why should he go there? No, sir; turbulence and unhappiness are inseparable companions in human breasts, and peace and pleasantness are associated and have been for all time. Give these people content, treat them with justice, and you shall have the fruit of such treatment, peace and good order and strength and happiness for our entire country. Disregard these plain results, and the fruits will he borne that have been borne so plentifully, and which now are sought to be stopped only by a perpetuation and intensification of the very methods that have produced them.

Mr. President, I have not forgotten that this is the anniversary of a day of glory to the American arms, and the illustration of that glory and valor was in this same city of New Orleans. We all were proud of it; not in Louisiana more than Delaware—it was generally celebrated in every State; and to-day patriotic associations are meeting to keep alive the memories of the glory of our common country.

Mr. President, shall the glory of 1815 be altogether clouded and dimmed by the shame of 1875? Shall it be that those brave men who, against greatly disproportionate odds, defended the city of New Orleans against superior numbers of a foreign foe—shall those men have fought in vain? Shall the glory of New Orleans and the fact that she was the scene of honor to American arms be now clouded by being the scene of disgrace to the American arms? Sir, I trust not. I hope not. Ambition, misjudgment, and ignorance of civil rule, high partisan feeling, all may have combined to carry the executive branch of this Government and his soldiers thus far; but I believe that when his action is understood the American people will give him a command which lie shall hear and obey, and that he shall he forced to recede from the position he has taken, and to take his armed hand from the throat of that prostrate people, and let her people once more know, in the language of the hill of rights of the State of Massachusetts, that they live under “a government of laws and not of men.”