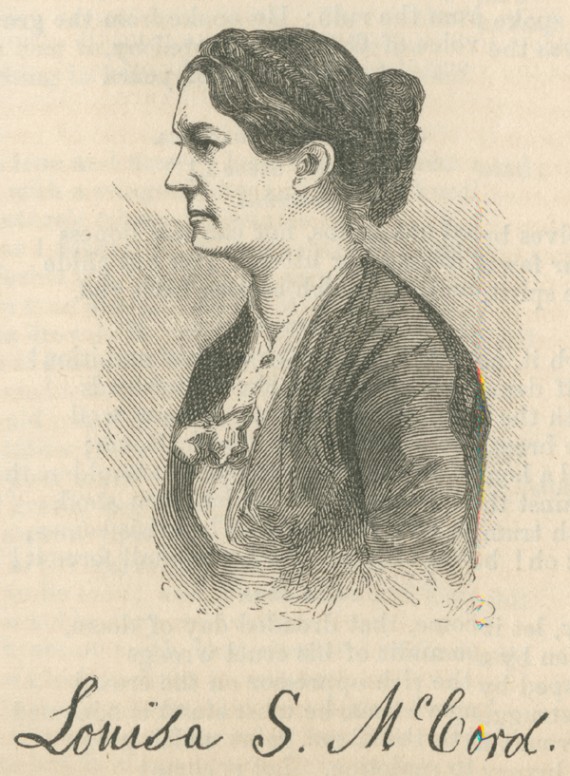

In her famous diary, Mary Chesnut called Mrs. Louisa S. McCord “the very cleverest woman” she knew. Of these two women from South Carolina, Chesnut is the most famous and widely read today, but Mrs. McCord—far more than clever—was a force to be reckoned with in her own time. In the antebellum era, she was the author of a number of forceful essays on political economy and social issues. Her other writings included poetry, reviews and a blank verse drama entitled Caius Gracchus. She also translated a book written by Frederic Bastiat, a French political economist, which was published in 1848 as Sophisms of the Protective Policy. Although Louisa S. McCord has been written about here and there in the 19th and early 20th centuries, it is only relatively recently that she has begun to receive her due recognition as one of the most significant thinkers of the antebellum South. Most importantly, in 1995 and 1996, her writings were collected and published in two volumes.

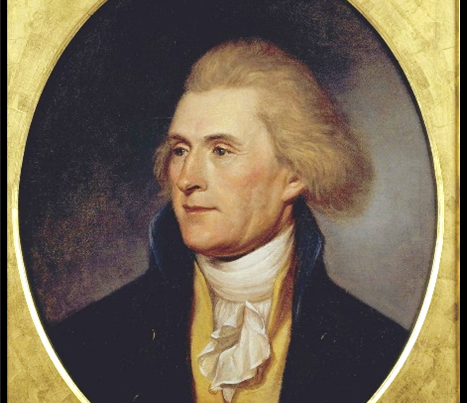

A 1993 anthology entitled the American Intellectual Tradition put Louisa S. McCord in the company of such persons as Jonathan Edwards, Thomas Jefferson, George Mason, John C. Calhoun, and other luminaries of 19th century America. The editors made the claim for her that she was “the most intellectually influential female author in the Old South and the only woman in antebellum America to write extensively about political economy and social theory.”

She was born in Charleston, S.C., on December 3, 1810. Her father, Langdon Cheves (1776-1857), an attorney and planter from Abbeville District, achieved national eminence as a statesman. Until the age of ten, Louisa received the usual education given to girls of her social class, but when it was discovered that she had an aptitude and passion for mathematics, family tradition has it that her father arranged for her to receive the same instruction as her brothers. While Langdon Cheves held federal offices, the family lived in Philadelphia, where she and her sister attended schools, Louisa becoming highly proficient in the French language. She also something of life in Washington, D.C. Describing another dimension of Louisa’s formative years, her cousin William Porcher Miles wrote of her: “The bent of her genius was rather for matters of state policy and political economy…Now was this strange when we consider the long public life of her father during which she was habitually thrown with the leading statesmen of the country…and heard so often discussed the then absorbing topics of ‘state rights,’ ‘free trade,’ ‘tariffs,’ and ‘banks.’”

In 1840 Louisa married David James McCord, a prominent lawyer, banker, author and editor of numerous legal works, and a state legislator. The fifteen years of Louisa’s marriage to David J. McCord before his death in 1855 were the richest and busiest for her in terms of her writing. During this period she was published in such journals as the Southern Quarterly, DeBow’s Review, the Southern Literary Gazette, and the Southern Literary Messenger. Her drama Caius Gracchus, a book of poetry entitled My Dreams, and her translation of Bastiat’s book were all published under her name, but her political and social essays and reviews were usually published anonymously, though some were signed with her initials, L.S.M.

As a thinker, Louisa S. McCord was conservative and classical. She wrote against abolitionists, feminists, and socialists. In her writings about political economy, she was a proponent of principles known as laissez-faire. According to historian Robert Duncan Bass, her translation of Frederick Bastiat’s book in 1848 “influenced all her subsequent political thinking.” Bastiat was a champion of the free market and wrote brilliant and devastating critiques of protectionism and government subsidies. He also emphasized the importance of private property, and argued that the rights of all in society are best served when property rights are respected.

The foreword to Mrs. McCord’s translation of Bastiat’s book, written by her husband, explained the importance of its subject matter, contending that it is needful for every citizen to understand that “it is not nature, but ignorance and bad government which limit the productive powers of industry, and that in fulfilling the duty of a legislator, public and not private interests should form the exclusive object of his legislation…he is not to frame systems and devise schemes for increasing the wealth and enjoyments of particular classes, but to apply himself to discover the sources of national wealth and universal prosperity…”

The foreword refers to what we call today “crony capitalism” and special interest groups. Such government favors and subsidies were policies advocated by the Whig Party in America, and later, the Republican Party, along with a nationalized banking system, internal improvements and protectionist tariffs. It was the object of Bastiat’s book, Sophisms of the Protective Policy, to refute plausible but incorrect arguments (that is, sophisms) advanced against free trade.

Bastiat not only criticized protectionists, but also socialism and the socialistic tendencies of his own government in France. In his essay “The Law” he wished the world to be rid of the socialists, concluding, “Away with their social laboratories, their governmental whims, their centralization, their tariffs, their universities, their State religions, their inflammatory or monopolizing banks, their limitations, their restrictions, their moralizations, and their equalization by taxation! And now, after having vainly inflicted upon the social body so many systems, let them end where they ought to have begun—reject all systems, and try liberty—liberty, which is an act of faith in God and in His work.”

In his essay called “Government” Bastiat asked the question “What is government?” He then he went on to state: “I have not the pleasure of knowing my reader, but I would stake ten to one, that for six months he has been making Utopias, and if so, that he is looking to Government for the realization of them.”

Mrs. McCord’s article “Justice and Fraternity” published in the Southern Quarterly Review in 1849, was a critique of socialism and Utopias enforced by law, and it drew heavily on an article of the same name by Bastiat. Though the rise of socialism and communism is popularly associated with a later period, towards the middle of the nineteenth century, both of these schools of thought were becoming influential, not just in Europe, but also in the United States—mainly in the North, where many new religious and social reform movements were proliferating. Unitarianism flourished in the northern states, while the South remained for the most part religiously orthodox and socially conservative. Writing about this phenomenon in a pamphlet published in 1857, southerner George Fitzhugh asked of the North:

Why have you Bloomers and Women’s Rights men, and strong-minded women, and Mormons, and anti-renters, and “vote myself a farm” men, Millerites and Spiritual Rappers, and Shakers…and Grahamites, and a thousand other superstitious and infidel isms at the North? Why is there faith in nothing, speculation about everything?

Later in his pamphlet Fitzhugh also mentioned the Transcendentalists, as well as the Atheists, Utopian Socialists and Communists. Horace Greeley, the famous newspaper editor and reformer, advocated socialism, and his colleague at the New York Tribune newspaper, Charles A. Dana, recruited Karl Marx as a contributor.

Bastiat’s defense of free trade likely resonated with Mrs. McCord as a Southerner, because American protectionism, mainly in the form of the tariff, had been one of the principal sources of conflict between the South and the North for many decades. It came to a head in the Tariff of Abominations and the Nullification Crisis in the early 1830s and never really went away. The Republican Party platform of 1860 called for “adjustments” to the tariff law, and for internal improvements. The promise of a protective tariff was a significant factor in the 1860 election and helped the Republicans secure the crucial electoral votes of Pennsylvania and win the presidency in November.

The war that began in 1861 ended most of Mrs. McCord’s literary efforts. She turned all her formidable energies instead to the support of the Confederate Army and became well known and highly revered in the state for her tireless work for the soldiers. The McCord house in Columbia, S.C., where she lived with her two daughters and a daughter-in-law, was adjacent to the campus of the South Carolina College, the location of the main Confederate hospital, and in time, part of Mrs. McCord’s home also became a hospital ward as well as a dining hall for the ambulatory patients. She was the president of the Soldiers’ Relief Association and the Ladies’ Clothing Association of that city. Her plantation, Lang Syne, provided cotton and food crops for the Confederacy, and she personally funded the uniforms and equipment for the company of soldiers led by her son Captain Langdon Cheves McCord, who gave his life for the cause of the South.

Like other South Carolinians, Mrs. McCord was deeply affected by the outcome of the war, which resulted in the destruction of a civilization she had valiantly tried to defend. The heart that had already broken by the death of her beloved son and her country, was broken again when she was finally persuaded to take the hated oath to the United States in order to sell her house in Columbia. For several years after the war she lived with various relations, and in 1871, she left South Carolina and resided for a while in Canada. Around 1877 she returned to Charleston to live with her daughter Louisa and her son-in-law Augustine T. Smythe. One of her last public writings was an appeal to the women of South Carolina to join in an effort to raise a monument to the state’s Confederate dead. This monument was unveiled in Columbia in 1879, the year that Mrs. McCord died.