It was the purchase of Louisiana, therefore, which gave impetus to a plan which had been creeping upon New England, aided and stimulated by the Essex Junto. They agreed that the inevitable consequences of the annexation of this vast territory would be to diminish the relative weight and influence of the Northern section; that it would aggravate the evils of slave representation and endanger the Union by the enfeebling extension of its line of defense against foreign-invasions. But the alternative to annexation was,—Louisiana and the mouth of the Mississippi in the possession of France under Napoleon Bonaparte.

The acquisition of Louisiana, although the immediate cause for this project of disunion, was not its only, nor even its most operative cause. The election of Mr. Jefferson to the Presidency had meant to those swayed by sectional feelings the triumph of the South over the North,—of the slave representation over the free. On party grounds it was the victory of professed democracy over Federalism. Louisiana was accepted as the battle ground, however, and from that point the war was waged.

Mr. Griswold, Representative from Connecticut, said in the House of Representatives, October, 1803: “The vast and unmanageable extent which the accession of Louisiana will give the United States; the consequent dispersion of our population, and the destruction of that balance of power which is so important to maintain between the Eastern and Western States, threatens, at no distant day, the subversion of our Union.” Plumer of New Hampshire, declared in the Senate: “Admit this Western World into the Union and you destroy, at once the weight and importance of the Eastern States, and compel them to establish a separate and independent empire.”

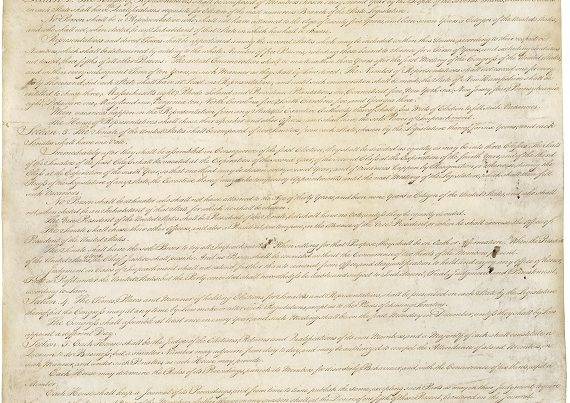

The Junto stoutly maintained, not only on the floor of Congress, but also among their constituents, that the balance of power between the North and South was disturbed. They became active in stirring up the Federal press of New England to clamor for separation, and by all the means in their power encouraged the leaders of their faction in Congress to lay plans for secession. Massachusetts was the leading commonwealth in raising the cry of disunion. The Massachusetts Federalists asked for an amendment to the Constitution which sets forth, at length, the principle that the Union of States could not exist on terms of inequality; that the representation of slaves was a concession of the East to the South, and that the representation was injurious and hurtful from the first. The advocates of the proposed amendment stoutly maintained that Massachusetts was in danger; that her sovereignty and her independence were swiftly and surely being taken away; that the power of the South over the North was due to slaves and that a crisis was at hand.” Thus the sons of Massachusetts argued that separation was the only means of preserving their independence.

In view of subsequent history, it is interesting to reflect that the earliest talk of disunion came from those who upheld and profited by the institution of slavery, but from men who were descendants of the founder of civil liberty in New England.

The disunion project was under secret discussion in the eastern quarter of the Union, fermented by those most hostile to the new order of things. It had its origin, as we have seen, in Washington where the New England coterie in Congress comprised ambitious and disappointed men.

The Connecticut Courant comments upon the situation as follows: “Although our National Government must fall a sacrifice to the folly of Democracy, and to the fraud and violence of Jacobinism, yet if our state governments can be preserved, tranquilty may yet be lengthened out. These observations are made in full view of that most deplorable event, the fall of the National Government. But, I hope that our state governments may yet be preserved from the claws of Jacobinism.” The Eastern Argus, on the other hand, hostile to the Junto movement, declares that the time has arrived when the cloven foot of Federalism has made its appearance without a covering. “The plots of these leaders of aristocracy,” it says, “have been showing their hideous deformity, at different periods, ever since the establishment of our Government. But that which discloses their ultimate design to overthrow our happy Government and establish a monarchy, appears in the declaration of Uriah Tracy, Senator from Connecticut.” The Argus goes on to quote the letter from Mr. Tracy to General Skinner “and others” in which he declared that, “Republican forms of government will never answer”—that “our Constitution is good for nothing,”—that, “the President and Senators must be hereditary,”—that, “it must be here as in Great Britain.”

Mr. Jefferson said: “The ‘Essex Junto’ alone desire separation. The majority of the Federalists do not aim at separation. Monarchy and separation is the policy of the Essex Federalists; Anglomany alone, that of those who call themselves Federalists. The last are as good Republicans as the brethren whom they oppose and differ only in their devotion to England and hatred of France imbibed from their leaders.” No one has given a better summary of the shattered Federalist desires than this.

The Junto had been working for some time without any central head or rallying point. They had no leader since Hamilton forsook them, and this had proved to be a great impediment and, perhaps, a greater blessing to the country. There was no organization working toward a desired end. They were simply trying to get as accurate an idea as possible of the sentiment of the people upon whom they must depend. They maintained the utmost secrecy and went about on their tiptoe lest the awful monster leading the opposing forces be acquainted with their plans. They were sensible of the fact, however, that there must be some central point around which they could cluster, and someone as reckless as themselves to lead. I think we can say that Mr. Pickering, from this time, assumes the position of leader and does more than any other man to effect their schemes.

In a letter to Mr. Cabot, Pickering gives us a pretty clear idea what the Junto had in mind and what they hoped to accomplish. To quote him:

The last refuge of Federalism is New England, and immediate exertion, perhaps, its only hope. It must begin in Massachusetts. The proposition would be welcomed in Connecticut; and we doubt of New Hampshire? But New York must be associated; and how is her concurrence to be obtained? She must be made the center of the confederacy}- Vermont and New Jersey would follow, of course, and Rhode Island of necessity. Who can be consulted, who will take the lead? The Legislatures of Massachusetts and Connecticut meet in May, and of New Hampshire in June.

The subject has engaged the contemplation of many. The gentlemen of Connecticut have seriously meditated on it. We suppose the British provinces in Canada and Nova Scotia, at no remote period, perhaps, without delay, and with the assent of Great Britain, may become members of the Northern Confederacy. Certainly that Government can only feel disgust at our present rulers. She will be pleased to see them crestfallen. She will not regret the proposed division of the Empire. A liberal treaty of Amity and Commerce will form a bond of Union between Great Britain and the Northern Confederacy highly useful to both.

Mr. J. Q. Adams, a member of Congress says that during the Spring Session of 1804, the author of the written plan was named to him by Mr. Tracy. And that he was a distinguished citizen of Connecticut. “I was told,” says Adams, “it originated there; had been communicated to individuals at Boston, at New York, and at Washington.” The plan, according to Mr. Adams, had three alternatives of boundary. ” 1. If possible, the boundary was to extend to the Potomac, 2. to the Susquehanna, 3. to the Hudson. That is, the Northern Confederacy was to extend, if it should be found practicable, so as to include Maryland. This was the maximum. The Hudson, that is, New England and a part of New York, was the minimum. The Susquehanna, or Pennsylvania, was the middle term.” The plan, if possible, was evidently destroyed.

In the life of Mr. Plumer by his son, various extracts are given from his contemporary journals and correspondence, exhibiting special and definite particulars of the plan of disunion, and of interview in reference to it with its projectors and followers. “I recollect and am certain,” says Plumer, “that on returning early one evening from dining with Aaron Burr, Mr. Hillhouse, after saying to me that New England had no influence in the Government added that, ‘The Eastern States must and will dissolve the Union, and form a separate government, and the sooner the better. But I think the first man who mentioned the subject to me was Samuel Hunt, a Representative from New Hampshire. He conversed often and long upon the subject. He was very eager for the Northern Confederacy and thought it could be effected peaceably and entered into a detailed plan for effecting it. I often talked with Robert Griswold. He was, perhaps, the most eager of all whom I talked with, and was practically of the same opinion as Mr. Hunt. Next to Griswold, Uriah Tracy conversed most freely and fully regarding the plan. It was he who informed me that Hamilton had consented to attend a meeting of select Federalists at Boston, in the autumn of 1804. Mr. Pickering told me of the plan while we were walking around the northerly and easterly lines of the city.”

Under date of November 23, 1806, Plumer mentions in his journal, that in the winter of 1804, Pickering, Hillhouse, and himself dined with Aaron Burr; that Hillhouse, “unequivocally declared that it was his opinion that the United States would soon form two distinct governments”; that “Mr. Burr conversed very freely on the subject”; “and the impression made on his (Plumer’s) mind was, that Burr not only thought a separation would not only take place but that it was necessary.” Yet,” he says, “on returning to my lodgings and critically analyzing his words, there was nothing in them that committed him in any way.” These quotations leave us no longer in doubt as to where the conspiracy began and that there were a great many plans being made. These plans, we regret to say, were hatched in the National Congress and by some of its ablest members.

The Junto seems not to have overlooked the fact that considerable expense would be attached to their plan and Robert Griswold, according to Mr. Pickering, made a careful examination of the finances. He found that the States above mentioned, to be embraced by the Northern Confederacy, were then paying as much, or more, of the public revenues as would discharge their share of the public debt due those states and abroad, leaving out the millions given for Louisiana. In the same letter he assumes that our mutual wants would render a friendly and commercial intercourse inevitable; that the Southern States would require naval protection of the Northern Union, and that the products of the former would be important to the navigation and commerce of the latter.

Many of the Junto believed that separation could be brought about peaceably. Indeed, they had a perfect right to think so for the right of secession had not been very seriously questioned at this time. The Constitution was in its infancy and no one seems to have had a very clear idea just what it could be made to cover. Secession, therefore, was not held to be an unpardonable sin. It was spoken of frequently on the floors of Congress and no one was censured for such utterances.

But in case forceful means should be necessary they looked to General Hamilton as military leader. We can scarcely believe that Hamilton had consented to this, for he disapproved of the plan. It is very likely, however, that the Junto expected it of him and he may have given his consent. It is interesting to reflect whether or not, in view of his expressed sentiments on the subject of separation, he would have listened to a call to lead forces of a Northern Confederacy against the South and West, if such a crisis had arisen. Would his patriotism have wavered when weighed in the balance against his military ambitions? Eager as he was for military glory, the prospects would not have been sufficiently alluring to satisfy his ambitious desires. He wished to lead a great National army and nothing less would have sufficed.

Therefore, with their plans fairly complete, the Junto began again, without any open organization, to apprise their innocent constituents of these plans and to ascertain, as far as possible, just what percentage could be depended on to follow them into the proposed haven of rest. Their mode of enlightenment was a secret correspondence. These letters are full of the vilest denunciations of Jefferson and his policies. Any one who may desire to read them will be convinced that our present-day politicians have tongues and pens unusually discrete when compared to this minority wing of that once dominant party.

The Federal editors, who under the late administration were devoted to the principles of passive obedience and who enforced the necessity of unqualified submission to the Constituted authorities, were soon imbued with Juntoism. These same editors, therefore, in 1803 were in the true spirit of disorganization, vilifying the President and administration and further encouraging the people to resist the Constituted authorities.

One of their bitterest thrusts was leveled against Jefferson for unseating their “midnight judges.” They claimed that he was surely destroying the Constitution with an eye single to his own glory and to that of the common folk. This proved to be always an effective argument, even though called from the past. The Louisiana purchase, of course, was proclaimed to be a destruction of that balance of power, established and ordained, once and forever, by the framers of the Constitution. The new Constitutional Amendment, they purported to believe was solely a party amendment designed to keep Republican in office to the complete exclusion of Federalists. But perhaps the weightiest argument of all was what they termed the “Virginia influence.” This influence, they claimed, supported every suggestion of Jefferson’s and could only be broken up by a dissolution of the Union.”

The Vermont Centinel, November 21, 1804, has the following to say regarding the popularity of the recent amendment: “The recent excellent amendment to the Constitution proves that Mr. Jefferson’s Administration has been the most popular that the United States has ever experienced. Fourteen of the seventeen free and independent states adopted the Amendment, some unanimously, too.” No possible objection could justly have been found to an amendment simply providing that it be specified which candidate was to be President and which Vice-President. The other points need no comment.

But, the lack of a regular leader had not been the only obstacle in the way of success for the Junto’s plans. There were some of the members who agreed that New England was unprepared and that there must be a more definite and widespread complaint before she could act. George Cabot said: “It is not practicable without the intervention of some cause which would be very generally felt and distinctly understood as chargeable to the misconduct of our Southern masters; such for example, as a war with Great Britain manifestly provoked by our rulers.”

Tapping Reeve commented sarcastically upon their “unpreparedness” as pointed out by Cabot and suggested that, if the members in Congress would come out with glowing comments upon the ruinous tendencies of the measures of the Administration before the sitting of the Legislatures, that would bring about all the “preparedness” necessary. In the same letter Reeve suggested a very ingenious plan by which a foundation might be laid for separation. “I do not know,” he says, “in what manner this separation is to be accomplished unless the Amendment is adopted by three-fourths of the legislatures, and rejected by Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Connecticut upon the last ground taken by Delaware. In such case, I can see a foundation laid.” Presumably he meant by this, that if several of the New England States would reject it as not having been passed by a two-thirds vote of Congress, the people would immediately fall in line and clamor for seperation. The problem confronting the Junto was how to get the people prepared and willing to follow them. However firmly convinced that their plan was good, they found many a “doubting Thomas” and this work progressed slowly.

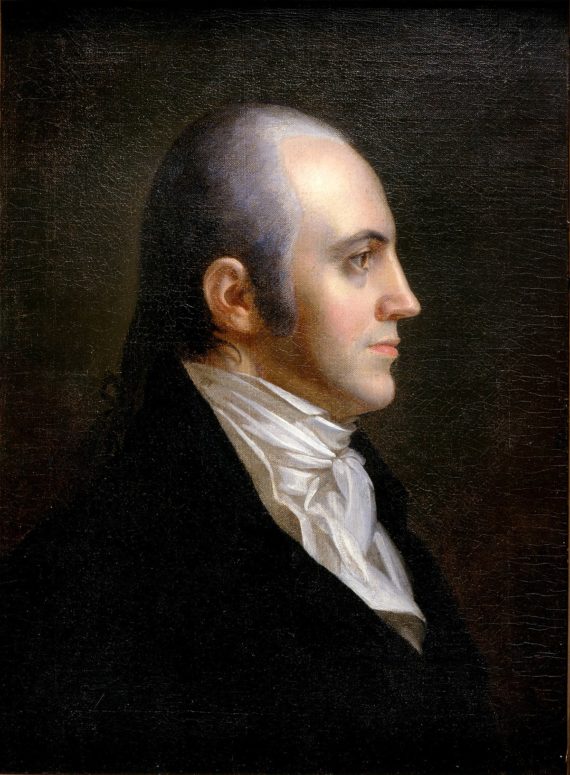

It has been shown that the Junto believed it to be absolutely necessary that New York be made the central point of the Confederacy. The question, therefore, was how to get control of it. They must capture New York and find some one to lead in the final dash. Pickering, although never wanting in argument, was not the person, they felt, to place at the head of their Confederacy. At length they saw a chance to elect Aaron Burr Governor of New York, and, in this way, establish the man they most despised as leader and ruler of the Northern Union.

The silent but persistent determination of Jefferson’s friends to force Burr into retirement produced much bitterness in New York, where the Vice-President had a nest of young followers gaping for office. There was no effort to re-nominate Burr for the Vice-Presidency. Governor Clinton, the new nominee for the office, declined to be re-nominated as New York’s Governor. It became necessary, therefore, to choose a candidate for the Governorship. The regular Republican nomination fell upon Chief Justice Lewis. The opposing faction of the same party nominated Aaron Burr, with the confident expectation that the Federalists would cast their votes for him.

It was the work of the Burrites in New York that opened the way for the Junto. Before Congress adjourned, therefore, the Eastern separatists conferred with Burr regarding the situation in New York. They believed that Mr. Burr ought to commit himself definitely to other policies if they should consent to throw all of their weight into the contest and elect him. The Junto knew that they could not, even in conjunction with the New York Federalists, elect a Governor because the last election had exhibited so large a Republican majority. But they saw a chance, in conjunction with the Burrites, to elect Mr. Burr, thereby scoring two points: (1) The capture of New York for the center of their Union; (2) the election of a man whose only virtue, in their opinion, was that he was unscrupulous enough to do their bidding.

Mr. Griswold made an engagement to call on Burr in New York after the close of Congress. Griswold wrote Wolcott saying: “Burr has expressed a wish to see me, and to converse, but his situation in this place does not admit of it; and he begged me to call on him in New York. Indeed, I do not see how he can avoid a free and full explanation with Federal men.” According to Hamilton’s Republic the interview took place between Griswold and Burr at the home of the latter in New York, on the 4th of April. And with the same cautious non-committal he had shown during the Presidential election, Burr stated that he must go on as a democrat to obtain the Government; that, if he succeeded, he would administer it in a manner that would be satisfactory to the Federalists. In respect to the affairs of the Union Burr said: “The Northern States must be governed by Virginia, or govern Virginia, and there is no middle course.”

In the letter, referred to above, Griswold adds: “He (Burr) speaks in the most bitter terms of the Virginia faction, and of the necessity of a Union at the Northward to resist it; and it may be presumed that the support given to him by Federal men would tend to reconcile the feeling of those Democrats who are becoming dissatisfied with their Southern masters.” Thus they were forced to accept Burr in a “Just as I am” attitude. It was too great a chance, however, to be recklessly flung away. So the Junto aid and the influence were tendered Burr with hope pitted against fate.

The question then arises, by what great process of juggling patriotism and statesmanship, could a few New England Federalists control an election in New York? By what great stretch of moral principles could they relieve their consciences after thrusting such a character as Aaron Burr upon New York as Governor? We will again quote Robert Griswold for our answer. “Although the people of New England,” he says, “have not on ordinary occasions, a right to give an opinion in regard to New York, yet upon this occasion we are almost as deeply interested as the people of that state can be. If any other project can be fallen upon which will produce the effect desired of creating a union of Northern States, I should certainly prefer it. … The election of Colonel Burr is the only hope which, at this time presents itself of rallying in defense of the Northern States.”

Mr. Pickering in his attempt to influence Rufus King wrote from Washington, March 4, 1804: “The Federalists here, in general, anxiously desire the election of Mr. Burr to the Chair of New York; for they despair of a present ascendancy of the Federal party. Mr. Burr alone, we think, can break your Democratic phalanx; and we anticipate much good from his success.

Were New York detached (as under his administration it would be) from the Virginia influence, the Union would be benefited. Jefferson would be forced to observe some caution and forbearance in his measures.” Pickering evidently meant that the Northern Union would be much more likely to succeed.

There is one figure that we must not lose sight of who was able, at any moment, to stay or forward the plot of the Junto. Alexander Hamilton leading a quiet life at his home in New York was watching the movement of the New England Federalists with an eagle’s eye, ready to swoop down and devour their dearest plans if they did not accord with his ideas. Hamilton was the man whose yea or nay, at this critical moment, could decide the destiny of the Union. There is not the slightest doubt that his and only his leadership, could rally the New York people to action. Once he had defeated Aaron Burr and the Junto; would he do it again?

About the time the nominations were being made in New York a few leading Federalists held an informal conference at Albany to consider the expediency of either nominating a Federalist candidate, or if this should not prove expedient, of supporting either of their opponents’ candidates. Hamilton knowing the intention of the Junto, and viewing it as a question far beyond the politics of New York, was present. To his mind it was a question of the preservation or of the dissolution of the Union. He read, therefore, a paper of very great importance before the conference, entitled: “Reasons why it is desirable that Mr. Lansing, rather than Colonel Burr, should succeed.” The point which Mr. Hamilton made in this paper was that Mr. Burr had always pursued the track of Democratic politics. This, he had done either from principle or from calculation. If the former he would not at that time change his plan when the Federalists were prostrate. If the latter, he certainly would not relinquish the ladder of his ambition, and espouse the cause of a weaker party. He went further, however, and said that, “It would probably suit Mr. Burr’s views to promote this result, to be the chief of the Northern Portion; and, placed at the head of the State of New York, no man would be more likely to succeed.” Hamilton contended that Burr would not be true to his promises, if he had made any to the Federalists, but when they had elevated him to power in New York, he would desert them, and simply use his office to form a greater Democratic wing in the North, in opposition to the Jefferson wing, in the hope of being the next President.

In spite of Hamilton’s protests the Burr press, two days after Burr’s nomination as Governor, opened with the following: “Burr is the man who must be supported or the weight of the Northern States in the scale of the Union is irrecoverably lost. If the southern and particularly the Virginia interests, are allowed to destroy this man, we may give up all hope of ever furnishing a President to the United States.”

Jefferson had divined their scheme from the coalition of the Eastern Federalists with the Burrites; but it gave him no uneasiness. “The object,” he said, “of the Federalists is to divide the Republicans, join the majority, and barter with them for the cloak of their name; . . . the price is simple. . . . The idea is clearly to form a basis of a separation of the Union.”

What a deplorable and dangerous state of affairs! The Junto supporting Burr as the only hope of carrying through their Northern Confederacy plot; the New York wing of the Republican party, or the Burrites, supporting him in opposition to Virginia influence, as the only hope of ever furnishing a President to the United States. One contemplating a dissolution of the Union with Burr as leader of the northern section; the other hoping, at some future day, to elect this dangerous man President of the United States. Either scheme, if successful, would have been disastrous. Colonel Burr’s prospects, too, seemed to assume an imposing prospect. His Republican friends in New York, though not numerous, were talented, industrious and indefatigable in their exertions; and in view of Federal support, his chances were very encouraging.

The election was carried by the united friends of the administration, Lewis receiving 35,000 votes, while Burr received 28,ooo. Mr. Burr undoubtedly received a very considerable number of Republican votes; he failed, however, in consequence of the defection of a portion of the Federal party. This element of the Federal party was controlled and influenced by the paper read at Albany, just before the nomination, by Alexander Hamilton. It was New York’s portion of the Federal party which the Junto could not control. Hamilton’s prophecy, that no reliance could be placed in Burr, had very great weight with this class of voters. It was that class whom the Federalists claimed should have nothing to do with the Government.

It was Mr. Hamilton’s paper, therefore, coupled with the sound judgment of the New York Federalists, that defeated Aaron Burr. This was the second time that Hamilton had come to the rescue of his country and defeated Aaron Burr; twice he had defeated the “Essex Junto”; but it was the last defeat for Burr’s bullet was soon to place his most bitter rival beyond the vale of political strife. Hamilton was the barrier over which the dizzy ambitions of the Union breakers could not climb. Burr’r political defeat, followed by Hamilton’s tragic death, therefore, checked the Eastern Confederacy plot in its first state of development. This proved to be the greatest blow that had yet befallen the Junto and its members sank into deep despair. Unfortunately, however, there was a later growth from the same root. The plan of separation was not abandoned but only allowed to lie dormant for a while. “Not dead but sleepeth.”

The returns of the national election proved beyond question that the Eastern Federalists had no national issue against the administration which had been peaceful, popular, and very successful. Jefferson and Clinton swept the country with ease in November carrying the greater part of New England, Massachusetts unexpectedly included. Pinckney and King did not get an electoral vote in their respective states. Connecticut, Delaware, and two votes from Maryland gave them 14 against 162 for Jefferson and Clinton. The election proved very clearly that Mr. Griswold’s fears were not without foundation when he said: “Whilst we are waiting for the time to arrive in New England, it is certain that Democracy is making daily inroads upon us, and our means of resistance are becoming less every day.” The Republicans were daily creeping up to the very doors of the Junto; Vermont and Rhode Island having gone Republican in the State elections, and the National election being so decisive, it showed up the plotters in a light that needs no comment and is severe enough.

Throughout the period from 1800 to 1808, Massachusetts changed her method of choosing her electors three times. Governor Strong, in 1800, sanctioned a resolve to have the Legislature choose the electors of the President and Vice-President. A republican addressing the electors in 1805, declared that this sanction had been influenced by the Junto for the purpose of excluding a* Republican from the Presidency. In 1804, the Junto discovered that electors had best be elected by general ticket in order to preserve the Constitution and the liberty of the people. But again in 1808, the spirit of the Constitution and the rights of the people required that the choice should be transferred from the people to a federal majority in the Legislature, which majority being the Essex Junto, could by no means represent the character of the State.

The remarkable facility with which the Junto could destroy systems without substituting anything, reminds one of the words of a pious Connecticut priest: “Even hogs,” said he, “can root up a garden; but they can never plant one.”