Those of us whose experience goes back a way into the last century, can remember when “democracy” was the main theme of American discourse. A million tongues proudly and repeatedly declared that America was the Democracy, exemplar and defender of that sacred idea to all the world. Hardly anyone dared to question that sentiment. It saw us through two world wars and the Cold War.

Of course, praise of “democracy” was not always sincere, and the term never had a very strict and clear definition. But most Americans thought of it in Lincoln’s sonorous phrase: government of, by, and for the people. In practical terms that seemed to mean majority rule. In that case Lincoln was not sincere because he headed the party of a large minority that seized control of the federal government and made brutal war against another large minority of the people.

Of course, a lot of questions were bypassed in the celebration of “democracy.” Who are “the people”? Who gets to participate in majority rule? Our Founding Fathers, like the ancients, were wary of a too pure democracy. They would have been astounded by the notion that a few million uninvited immigrants could wade ashore and immediately become deciding members of “the people.”

The Founders preferred to consider themselves “republicans,” not “democrats.” For republicans “the people” were not the mass but citizens with substantial stakes in society. Some, the Hamiltonians, thought that pure majority rule simply meant that the poor majority would vote themselves the wealth of the rich minority, that the people are “a great beast.” Therefore, the majority had to be hedged about by Supreme Courts, infrequent elections, a strong executive with armed force, government bondholders, and a national bank. Hamiltonianism now universally prevails, except that the constitutional gadgets that they relied on have never quite worked as they are supposed to. They would undoubtedly be shocked at some of the purposes of social revolution to which radicalized elites have devoted their institutional power.

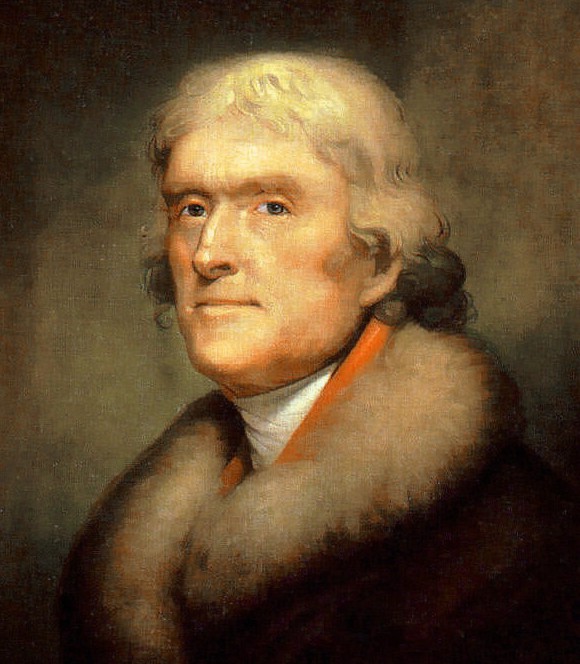

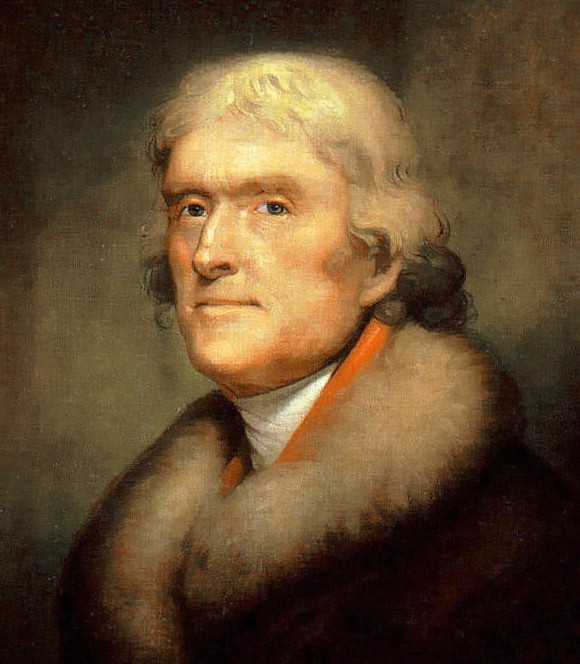

The Jeffersonians had a bit more trust in the people and the ability of the majority to decide justly. After all, most folks were busy making a living and did not bother the government as long as it did not bother them. It was elitists who hung around the halls of power looking for privilege and profit. However, it cannot be over-stressed that the government in which the majority was to rule was one of very limited power. It was the agent of certain collective tasks but had no power to seriously interfere with the natural society of those who deserved to be called free men. For Jeffersonians majority rule was very limited in its jurisdiction, and the farther away it was the more limited it should be.

The thoughtful have always understood that there is a tension between democracy and liberty. They do not naturally go together, in fact are logically in conflict. Democracy strictly considered has nothing to say about liberty. However, Anglo-Saxon historical experience had for some time provided what seemed to be a practical working relationship, so it was somewhat natural to think of “democracy” being the two things happily married.

Looking a step further ahead, we find in our path another powerful idea: equality. Majority rule suggested that citizens were more or less equal in their political rights and freedoms. But both ancients and the Founders were pretty clearly convinced that liberty and equality were natural enemies and very unnatural companions.

We no longer talk much about “democracy,” but Equality is all the rage. Minorities are to be made “equal” by government force: majority will and constitutional limitations be damned. Aspiring politicians no longer promise just rule and following the will of “the people” but announce what government power they will use to enforce Equality. Democracy, majority rule, the will of the people are obsolete ideas that stand in the way of sacred Equality.

Thus, Obama can disdain the people for their “guns and Bibles” and Hillary Clinton, like Alexander Hamilton, can describe the people as “deplorables.” In a genuine government of the people both of these characters would be sent down in shame for insulting “the people.” Instead, they gather the votes of a majority of the electorate. How can this happen? I offer a possible explanation. The American educational system has turned out millions of pseudo-intellectuals, people with no particular intelligence or learning and who have no real power but who think that because they share the egalitarian scripture that they are therefore members of the elite and superior to those deplorables.

In present day America vast amounts of the national wealth are owned by a tiny fraction of people; imperial military bases straddle the globe; and five Supreme Court justices can make social revolutions in defiance of law, tradition, religion, and common sense. A private banking cartel controls the credit and currency of the country; the flow of information is effectively controlled by a few unknown oligarchs; there is an unpayable government debt that can never be paid, is partly owned by foreign powers, and will economically enslave our descendants; there is no civilized democratic political debate but only advertising campaigns competing for market share.

This cannot possibly be a government of the people, a democracy. It is even an enemy of genuine equality of citizenship. We should stop pretending we are a democracy, but that would be an intolerable blow to American self-esteem which has long been based on denial of reality.