In a penitent act of fiscal flagellation, Harvard University recently reported that it was establishing a hundred million dollar “Legacy of Slavery Fund” in an effort to atone for its century and half history of using enslaved people. In the report, it was cited that from its founding in 1636 until 1783, when the Massachusetts Supreme Court declared slavery to be illegal in the state, the university had slaves working on its campus. Slavery in the Boston area had, however, existed prior to Harvard’s founding, or even that of the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630.

Two years after the Pilgrims had established their Plymouth Colony in 1620, a second British colony was started in an area south of Boston by a London merchant, Thomas Weston. As a business venture, he and sixty male colonists attempted to develop a large plantation in what is now the city of Weymouth, but their effort failed and the colony was abandoned in the latter part of 1622. The following year, a captain in the British Navy, Robert Gorges, was named governor general of New England and he began another colony on the same site. Gorges wanted a more permanent settlement though and brought with him a number of families.

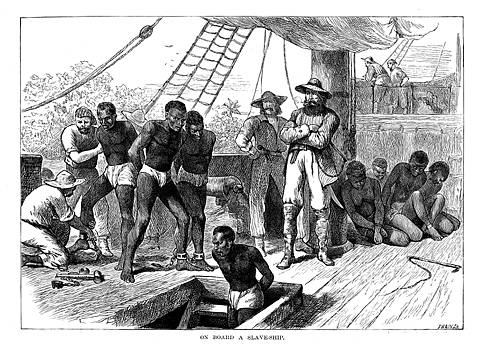

One of the colony’s settlers, Samuel Maverick, also brought with him three African slaves, a man and two women . . . the first in the New England colonies. While Gorges’ colony also failed, Maverick, his slaves and a few other colonists remained but later they all relocated to Boston after the colony there had been established. According to a 1671 book by an English traveler to Boston, John Josselyn, Maverick also attempted to breed his slaves and sell their offsprings.

Today’s rewriting of history, the “1619 Project” in particular, would have one believe that the first black slaves in America were the Africans brought to Virginia that year. Those Africans, however, were actually slaves who were being taken to the colonies in Latin America by a Portuguese slaver. Following the slave ship’s capture in the Caribbean by a British privateer, they became indentured servants after being taken to Jamestown and were thus able to gain their freedom after a period of servitude.

This was not the case in relation to the three black slaves brought to New England by Samuel Maverick four years later. They not only remained slaves but became the forerunners of both the North’s large slave population and the New England slave trade started by Maverick that was expanded into a major industry by those who followed him. Many of the later slave traders were prominent figures in New England’s early history, such as Jonathan Belcher, a Harvard graduate who was the colonial governor of Massachusetts and New Hampshire from 1730 to 1741 and later the governor of New Jersey from 1747 to 1757.

Another Bostonian who made his fortune in the African slave trade was Peter Faneuil. He later became one of the colony’s leading philanthropists who donated the market hall bearing his name to the city in 1740. That building became the venue for secessionist meetings held prior to the Revolutionary War and is now dubbed America’s “Cradle of Liberty.”

The Cabot family, one of the best known and most highly respected names in Boston, also derived much of its fortune from the slave trade stared by John Cabot and his son Joseph in the Eighteenth Century. The shipping of slaves from Africa, as well as the transport of rum and opium, was later carried on by Joseph’s three sons until the Atlantic slave trade officially ended on January 1, 1808.

While not a slave trader, John Winthrop, one of the founders of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and its governor for twelve years, did own slaves and in 1641, he served on the committee that wrote the colony’s first guiding laws, the Body of Liberties, a section of which legalized slavery in Massachusetts.

In regard to the connection between slavery and New England’s institutions of higher learning, all four of the area’s colonial colleges, including New College (Harvard) in Boston, had such involvement. At Harvard, beginning with its initial schoolmaster, Nathaniel Eaton, at whose home in Boston were held the college’s first classes, many of the administrators, faculty members and staff, as well as students, owned slaves in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Three of the colony’s governors who served as Harvard’s overseers, John Winthrop, John Leverett and Joseph Dudley, also owned slaves, as did John Hancock, the first to sign the Declaration of Independence in 1776, who was the school’s treasurer from 1773 to 1777.

Furthermore, some of Harvard’s major donors were not only large slave owners, but slave traders as well. Among these was Isaac Royall who founded the professorship that later served as the foundation for the Harvard Law School. Royall owned over sixty slaves in Massachusetts and with his father, many more at plantations on Antigua in the West Indies. Three other donors in the slave trade who also ran plantations in the Caribbean were James, Thomas and Samuel Perkins. Their contributions began Harvard’s School of Divinity.

Even though the primary benefactor of the Collegiate School (Yale University) in Connecticut, Boston-born Elihu Root, neither owned any slaves nor profited personally from their sale and was even opposed to the practice, he had been deeply involved. During his term as president of the British West Indies Company’s Fort George facility in India from 1687 to 1692, Yale had been responsible for managing the company’s extensive slave trade. On the other hand, the founder of Dartmouth College in New Hampshire Province, Eleazar Wheelock, did own about twenty slaves and his wife Maria Suhm’s grandfather, the Danish governor of Saint Thomas in the West Indies, both traded in slaves and had many working on his vast plantation there.

Perhaps the best example of a colonial college slave connection would be the College of Rhode Island (Brown University). That institution was founded in 1769 by and later named for New England’s most prominent slave traders, six brothers from Providence, James, Obadiah, Nicholas, John, Joseph and Moses Brown. The Brown brothers’ vast shipping company, the largest in New England, pioneered the infamous “Atlantic triangle trade” that carried rum and other goods from New England to the west coast of Africa, there to be traded for slaves that were transported back to South and North America for sale. The initial college buildings in Rhode Island were also built with slave labor and many connected with the school were either large slave owners or captains of slave ships.

Such history clearly shows that America’s first actual slaves were not those who were brought to Virginia in 1619 and became indentured servants there, but the ones in Massachusetts who remained slaves. History also indicates that it was the ships from New England’s ports, not any from the South, that carried their human cargoes from Africa to America for well over a century. A closer look at history would further reveal that, unlike the North, there was no actual slavery in the South until the mid-Seventeenth Century . . . July 9, 1640, to be precise.

On that date, an African indentured servant on a plantation owned by Hugh Gwyn, a member of Virginia’s House of Burgesses, was brought before the General Court of the Virginia Governor’s Council after running away to Maryland with two white servants. As punishment for their action, the two white servants were ordered to be given thirty lashes and to have their indentures extended for several years. The black servant, John Punch, was not only whipped thirty times but, unlike his white companions, was sentenced to serve Gwyn for “the time of his natural life.” Therefore, John Punch, fairly or not, became the South’s first legal slave.

As a sidebar, a similar court action involving another black indentured servant took place in Virginia fourteen years later. In that case, however, the servant, John Casor, merely refused to have his indenture extended and left to work for someone else. Casor’s original master, Joseph Johnson, sued the new employer and not only was Casor returned to Johnson, but the court also ordered that he remain in his master’s service for the rest of his life.

The primary difference in the Casor case, however, was that Johnson had formally been a black indentured servant himself and was one of the Africans brought to Jamestown in 1621. After gaining his freedom in 1634, Johnson purchased a large tract of land in Virginia and acquired five indentured servants, both black and white, one of whom being John Casor. In that 1654 court action, Johnson became the first of America’s many black slave owners and in time, about twelve per cent of Virginia’s free blacks owned slaves. By 1830, the U. S. census showed that at least ten thousand slaves throughout the nation were owned by free blacks.

Harvard’s introspective public soul searching and its large-scale funding to whitewash its black past may appear to be a sincere means of correcting the university’s long history of slavery and discrimination, but it is in reality merely another Northern act of faux contrition in relation to such matters. While those in the North may sometimes point a finger of mock self mortification at themselves, they still continue to cast the real blame for the roots of slavery and racism upon the South.

Moreover, those in the North, particularly in the field of education, also adamantly refuse to admit that the terrible war the North waged against the South a century and a half ago was not one to free the Southern slaves. Nor was the conflict even to preserve the Union, but one merely to save the federal tax base, as well as the economic life of the Northern states in which slave labor could no longer provide a legal or viable work force.

The primary difference in the Casor case was the lack of a criminal action on Casor’s part. Casor became a slave due to court decision in a civil trial.