The historians have put out another one of those ratings of Presidents – the great, the near great, etc. I always hoped that I would be asked to participate in that survey so I could start a boomlet for the truly greatest – John Tyler. But, alas, I was never asked. My disappointment has been assuaged, however, on seeing that LewRockwell.com has drawn attention once more to the important book Reassessing the Presidency, edited by John V. Denson. This book puts the subject into proper perspective.

Of course, the greatest Presidents, according to the Mainstream Intelligentsia (MSI), are those who grew the federal government the most and who exercised the most dictatorial power—that being their definition of greatness. The whole enterprise of such ratings has always seemed fishy to me. What do we mean, for instance, by Great? Genghis Kahn, Hitler, and Mao were great—in the sense that they made a great impact on history. Being Great in history is not necessarily a good thing. And greatness is surely a matter of perspective. Many may have profited from the doings of a great President, but there are also many who suffered. I doubt if very many of the 600,000 Americans who died in the War to Prevent Southern Independence would be all that enthusiastic about the greatness of Honest Abe Lincoln if they were allowed to vote.

As John Denson has written, the Presidency is a mirror of the progressive loss of freedom that has marked the history of the United States. The air is full of claptrap about presidential legacies. It is full of the declarations of fools that the current occupant of the executive mansion in the federal city is my president and our president, and our commander-in-chief.

The Founders of the American Union would have regarded all this as a sign of servility. In our worse times it is fearfully portentous of the spread of Führer worship. Constitutionally, the President is not the commander-in-chief of the country. He is not even the commander-in-chief of the government. He is merely the commander-in-chief (operations director) of the armed forces. And, constitutionally, the armed forces exist only as created by the Congress which must re-authorize their funding every two years.

Why does a President need a legacy? Isn’t it legacy enough that he did his job—that he obeyed and executed the laws honestly and competently and avoided getting the country into any unnecessary trouble? He was not supposed to be an object of worship, but simply a citizen who was to exercise power for a stated time and then retire once more to the body of the people.

When the MSI blather on about presidential legacies and presidential greatness, they reveal, among other things, their historical ignorance. The idea of presidential “greatness” hardly existed before Lincoln and really did not get a firm hold over national discourse until Teddy Roosevelt. Further, they fail to understand the reversal of values that has taken place. George Washington and Thomas Jefferson and even Andrew Jackson became president because they were great men; they were not great men because they became president or even necessarily great Presidents. Whereas their successors usually owe their greatness only to their luck in being able to manipulate a corrupt system well enough to be elected.

The lower end of presidential performers, according to the utterly predictable historians of the MSI, is occupied by those who failed to exercise dictatorial power. This reveals how ignorant of American history they are and how disdainful of democracy and Constitutionalism.

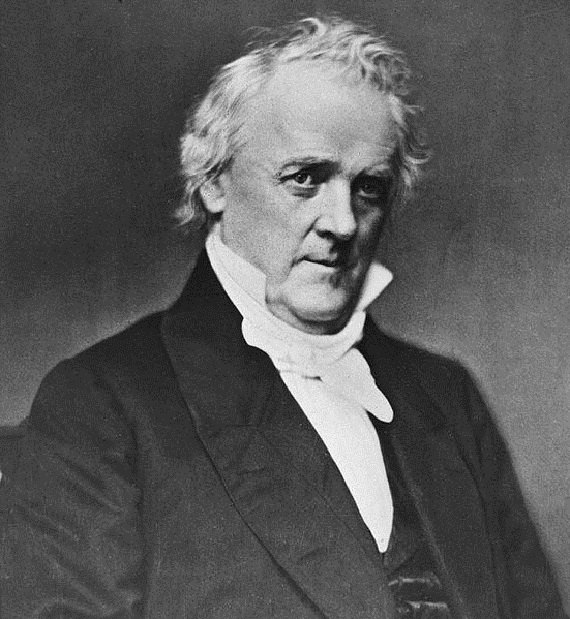

The worst of all Presidents, we are told, was James Buchanan, who failed to use force against the South to quash secession in 1860–61. This only works if we accept two assumptions: 1) Southerners are nonpersons who should be killed by the government if they resist it; 2) the government is a power eternal and self-justifying without any reference to limitations or to the consent of the governed. And of course, these are things that the MSI assume without question and without even noticing.

But James Buchanan’s world was not like that. Southerners were not criminals to be suppressed but Americans and fellow citizens—indeed good fellow citizens who had always contributed loyally and mightily to the American Union. They had enacted secession in an open, democratic, and constitutionally-based manner. A great many Northerners, like Buchanan himself, believed that the South had just grievances even if it had acted too rashly. In Buchanan’s world neither the President nor the federal government enjoyed unlimited power—he had been nominated and elected by a party that had made state rights its centerpiece since the time of Jefferson. The President and the federal government were limited to the powers expressly delegated to them, which did not include the power to make war on legitimate state governments and private citizens. Further, the government was not an eternal self-justifying force but rested on the “consent of the governed”—such consent being the bedrock American principle.

As a practical matter, Buchanan was aware that there were as yet more Southern people and states within the Union than out of it. They were not eager to rush into secession nor were they willing to countenance a brutal war of conquest against the seceded states, which they rightly regarded as an unprecedented atrocity that would destroy the Union in the guise of preserving it—and all in the interest of the state capitalist agenda of certain Northern elements. Not to mention that half of the officers of the army, and the better half, had already resigned or were in agreement with the Southern states that had not yet departed. With the position of the upper South and of vast numbers of Northerners who did not wish for the horror of civil war, there was plenty of room for negotiation. The obstacle to peace was the Republican party and its leader, who was glorying in his rise to power even as a minority candidate.

The Republican leader called for the invasion and conquest of the South, pretending that seven states were merely combinations of lawbreakers to be suppressed. The upper South seceded, more than doubling the resources of the rebels, the border states were put into bloody play, and the minority president reached for greatness by a seizure of powers that was previously unthinkable to Americans. Lincoln, in his narrowness and inexperience, seemed to think that 75,000 men could crush the rebellion though it eventually took a million men. It was either the biggest mistake or the biggest crime in American history. Heaven save us from such Greatness.

Copyright © 2007 LewRockwell.com. Reprinted by permission.