Mr. Leigh presented this paper at the 2019 Abbeville Institute Summer School on The New South.

Historians have reinterpreted Civil War Reconstruction over the past fifty years. Shortly before the Centennial it was commonly believed that the chief aim of the Republican-dominated Congress was to ensure lasting Party control of the federal government by creating a reliable voting bloc in the South for which improved racial status among blacks was a coupled, but secondary, objective. By the Sesquicentennial, however, it had become the accepted view that the Republican desire for racial equality was untainted by anything more than negligible self interest. Consequently, the presently dominant race-centric focus on Reconstruction minimizes factors that affected all Southerners of all races.

Contrary to popular belief Southern poverty has been a longer-lasting Civil War legacy than has segregation. Prior to the war the South had a bimodal wealth distribution with concentrations at the poles. The classic planters with fifty or more slaves had prosperous estates but they represented less than 1% of Southern families. Partly because 1860 slave property values represented half of Southern wealth, seven of the ten states with the highest per capita wealth joined the Confederacy.

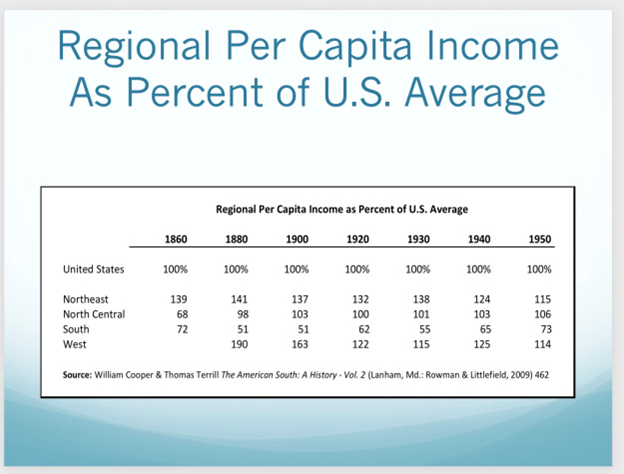

But since 70% of Confederate families did not own slaves, the South’s per capita income was 28% below the nation’s average. A century later eight of the ten states with the lowest per capita incomes were former Rebel states. The depths of post Civil War Southern poverty and its duration were far greater, longer, and more multiracial than is commonly supposed. It took eighty-five years until 1950 for the South’s per capita income to regain the below average percentile ranking it held in 1860.

The war had destroyed two-thirds of Southern railroads and livestock. Excluding the total loss in the value of slaves resulting from emancipation, assessed real property values in 1870 were less than half of those in 1860. About 300,000 white Southern males in the prime of adulthood died during the war and perhaps another 200,000 were incapacitated, representing almost 20% of the region’s approximate 2.8 million white males of all ages.

During the war, Southern farms had drifted back to nature. Returning Confederate soldiers often found that their families were starving.

Historian David L. Cohn adds:

When there was a shortage of work stock, the few surviving animals were passed from neighbor to neighbor. [When] there was no work stock [the men] hitched themselves to the plow. By ingenuity, backbreaking toil, and cruel self-denial thousands of Southern farmers survived reconstruction . . . They received no aid from any source, nor any sympathy outside the region.

By 1870, Southern bank capital totaled only $17 million, compared to $61 million in 1860. National policies largely ignored post-war Southern poverty until President Franklin Roosevelt commissioned a report in 1938, seventy-three years after the war had ended.

The study disclosed that the South remained America’s poorest region. Its 1937 per capita income of $300 was only half of the $600 for the rest of the country. Shortly after the Great Depression began, the president of General Motors voluntarily cut his annual salary from $500,000 to $340,000. His $160,000 cut was more than all the income taxes paid by two million Mississippi residents that year.

During the last year of the prosperous Roaring 1920s, Southern farmers earned an average of $190, which was only about one-third of the $530 average for other American farmers. As a result, there was often little money left for food and clothing and none for otherwise common articles such as books and radios.

Even as late as the 1930s, more than half of Southern farmers depended upon cotton alone. Yet price fluctuations in the World cotton markets were sheer gambles. Only once during the ten years between 1927 and 1937 did the price change less than 10% annually.

Composing more than half of all Southern farmers, tenants and sharecroppers were at the bottom of the heap. Many lived like the Russian serfs of the nineteenth century. Sharecropper per capita incomes averaged $63 annually which equated to $0.17 per day. By comparison, during the depression that followed the 1873 financial panic sixty-five years earlier, the Ohio Department of Labor estimated the poverty line at one dollar a day. Perhaps most surprising to present-day audiences, Roosevelt’s report disclosed that whites composed half of all sharecroppers and that they lived “under economic conditions almost identical with those of Negro sharecroppers.”

Since cotton was the cornerstone of the South’s economy nearly all residents shared the farmer’s hazards to some extent. Financing the farmers, for example, was more costly than elsewhere because of the greater risk of failure.

Poverty bred poor health. Ailments such a pellagra, rickets and hookworm that were almost unknown in other parts of the country plagued the South for almost a century after the Civil War. All could have been prevented by cheap dietary changes, better sanitation and the use of shoes. So short was the life expectancy in South Carolina that half of state’s population was under age twenty as late as 1930.

Of three million farm homes surveyed in 1930 only 6% had piped-in water. More than half were unpainted. Only about one-third had screens.

Post-war politics and federal economic policies contributed to the South’s long delayed economic recovery. Among such factors were property confiscations, Republican Party self-interest, discriminatory federal budgets, protective tariffs, Union veteran pensions, banking regulations, discriminatory freight rates, lax monopoly regulation, absentee ownership and the requirement that America’s poorest states pay for the public education of ex-slaves even though emancipation was a national—not regional—policy.

When Lee surrendered to Grant, more than two million fungible cotton bales lay scattered across the South as compared to a trifling $15 million in U. S. currency then circulating in the region. But instead of priming the pump of Southern economic recovery the cotton was plundered.

Union soldiers, U. S. treasury officials, and Northern businessmen stole most of it. A dismayed U. S. Treasury Secretary Hugh McCulloch remarked, “I am sure that I sent some honest cotton agents South, but it sometimes seems very doubtful that any of them remained honest very long.”

When the Civil War ended the Republican Party was barely ten years old. Its leaders worried that it might be strangled in its cradle if the re-admittance of Southern states into the Union failed to be managed in a way that would prevent Southerners from allying with Northern Democrats to regain control of the federal government. If all former Confederate states were admitted to the 39th Congress in December 1865 and each added member was a Democrat, the Republicans would lose their veto-proof two-thirds majority in Congress.

Thus, the infant GOP needed to ensure that most of the new Southern senators and congressmen be Republicans. That meant that vassal governments had to be formed in the Southern states. Since there were few white Republicans in the region the Party needed to create a new constituency.

Consequently, Republicans settled on two goals. First was mandatory African-American suffrage in all former Confederate states. The Party expected that such a mostly inexperienced electorate could be manipulated to consistently support Republican interests out of gratitude. Second was to deny political power to the Southern white classes most likely to oppose Republican policies.

Although it is often assumed that Republican Party sponsorship of Southern black suffrage was motivated by a moral impulse to promote racial equality, the bulk of the evidence suggests the Party was more interested in retaining political power.

First, the 1866 Civil Rights Act declared nearly all blacks to be citizens but expressly denied citizenship to Indians unless they paid taxes. Moreover, Chinese-Americans were also pragmatically excluded and would not even get the right to become naturalized citizens until 1943. Thus, the Act focused only on the solitary racial minority that was expected to be reliably Republican-loyal: ex-slaves.

Second, Republicans recognized that many Northerners opposed black suffrage in their own states. At the end of the War only five New England states with tiny black populations permitted blacks to vote. Connecticut, Minnesota, and Wisconsin rejected black suffrage in 1865. Kansas did so in 1867 as did Michigan and Missouri in 1868 and New York declined to repeal property requirements for black voters in 1869.

Third, a month after General Lee’s surrender, Union Major General William T. Sherman wrote a colleague, “I have never heard a negro ask for . . . [voting rights] . . . and I think it would be his ruin . . . I believe the whole idea of giving votes to the negroes is to create just that many votes to be used by others for political uses . . .”

Fourth, after the collapse of the Carpetbag regimes in 1877 the Republican Party virtually ignored Southern blacks.

As a result of their post-War lust for lasting political power the Republicans proceeded with a plan for universal black suffrage in the South, if not the North. They adopted three 1867 congressional acts and passed them over President Andrew Johnson’s vetoes. The acts imposed four requirements on the South.

First, except for Tennessee the remaining ten states of the former Confederacy were divided into five military districts and governed by martial law. Tennessee was exempted because she already had Republican-controlled government. President Andrew Johnson, who was from Tennessee, left it behind when moved to Washington to become Lincoln’s Vice President early in 1865. The rest of the Southern states had no civil governments while martial law ruled.

Second, each of the ten was to organize conventions to adopt new constitutions satisfactory to Congress. In order to optimize Republican-favorable results for the election of convention delegates, occupation soldiers were authorized to supervise voter registrations and administer loyalty oaths.

Third, the states were required to let black males vote for convention delegates and simultaneously deny office-holding privileges to many former Confederates and voting rights to those whites who could not take (pass) the loyalty oaths.

Fourth, each state constitution was to require universal black male suffrage although they were permitted to restrict white suffrage. Moreover, the general assemblies of the newly formed state governments might additionally restrict white suffrage after they were in session.

Although Congressional Republicans over-rode his objections, President Johnson’s veto messages cast doubt on the constitutionality of the 1867 Reconstruction Acts as well as the 1866 Civil Rights Act. Ever since the 1791 Tenth Amendment, voter qualifications had been universally regarded as a state’s right. In 1868, therefore, the Republicans resolved to amend the Constitution. The result was the Fourteenth Amendment, which had three key provisions.

First, persons born in the United States would be American citizens and citizens of their resident states. No race could be excluded, except non-taxpaying Indians. Asian-Americans, however, were also effectively excluded by gender-specific immigration restrictions. Specifically, few Asian females were allowed to enter the county for birthing babies that would entitle their offspring to birthright citizenship.

Second, states refusing suffrage to male citizens of any qualified race would have their congressional representation cut by subtracting the number of members of the excluded race from the applicable state’s population for purposes of calculating House representation and electoral votes. Due to their tiny black populations, the provision was inconsequential in Northern states.

Third, no elected representative from the former Confederate states could be seated in Congress until his state adopted the Fourteenth Amendment and Congress approved the pertinent state’s constitution. Until then, the applicable state would continue to be ruled by the military.

Secretary of State Seward ratified the Fourteenth Amendment in July 1868 by declaring that 28 of 36 states had approved it, even though two of the 28 (Ohio and New Jersey) had rescinded their ratifications. As a result, the 1868 Republican presidential candidate, Ulysses Grant, won 450,000 black Southern votes without which he would have lost the popular vote although he would have retained a majority of electoral votes. Notwithstanding his status of a Northern war hero, Grant failed to win a majority of America’s white votes.

Since six of the readmitted eight Southern states voted for Grant in 1868 and only two voted against him, it was apparent that a second amendment granting black men the vote in every state could be quickly approved. The resulting Fifteenth Amendment was ratified in 1870.

During Reconstruction former Confederates were required to pay their share of federal taxes for sizable budget items that if paid by an independent defeated foe would have been reparations. Although reparations are a common form of a victor’s compensation, nobody should assume that the Southern states escaped equivalent penalties merely because they were readmitted to the Union.

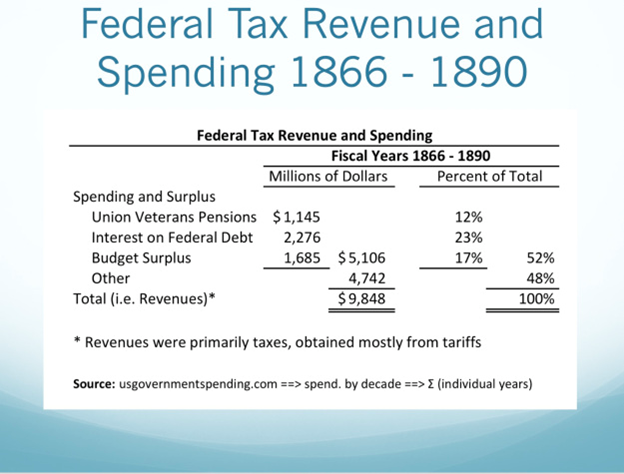

The above table summarizes federal tax revenues and spending for a quarter century following the Civil War. More than half of federal tax revenues were applied to three items:

(1) Interest on the federal debt.

(2) Budget surpluses used to retire the federal debt.

(3) Union veterans’ pensions.

Although compelled to pay their share of the taxes required to fund all those items, former Confederates derived no benefit from any of them.

The budget surpluses repaid the federal war debts, which had jumped 40-fold from $65 million at the start of the Civil War to $2.7 billion at the end. Southerners did not hold any of the bonds. Some were held by national banks, which bought them for monetary reserves as mandated by the 1863 National Banking Act, but many Northern civilians also owned the bonds.

Bond policies also penalized Southerners another way. Specifically, an 1869 law required that they be redeemed in gold even though Northern investors bought them during the War with paper money, which traded at a fluctuating discount to gold. Since the bonds and interest had to be paid in gold, the value of paper money required to make such payments was larger than the face amount of the bonds and their associated interest coupons. The difference was an extra cost to the taxpayer but a bonus to the Northern bondholder.

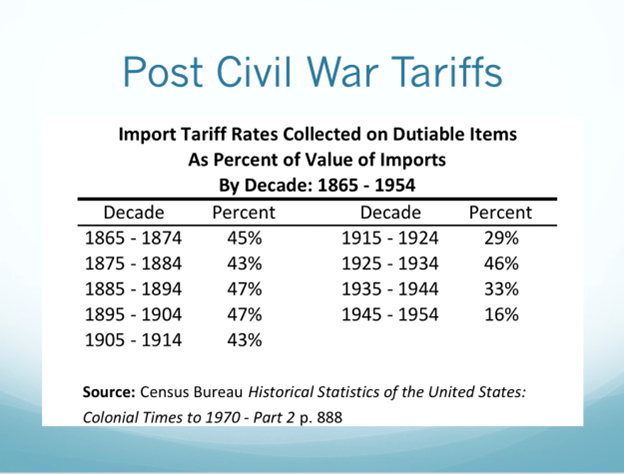

Protective tariffs caused the budget surpluses as they generated more income than needed to operate the federal government. As compared to 19% before the War, dutiable items were taxed at about 45% until after Democrat Woodrow Wilson became President in 1913. They were increased again in the 1920s after Republicans regained the White House. Rates generally remained high until after World War II when the manufacturing economies of the states North of the Ohio and Potomac rivers had no international competitors because World War II had destroyed the economies of Europe and Asia.

Protective tariffs harmed the South’s export economy. Even as late as the 1930s, the region sold 60% of its cotton overseas. But foreign buyers could not pay for Southern cotton unless they could generate exchange credits by selling manufactured goods to Americans, which protective tariffs restricted. By one estimate the post Civil War tariffs imposed an implicit 11% tax on agricultural exports. As Cornell professor Richard Bensel puts it, “[the tariff] redistributed [wealth] from the periphery to the [Northern industrial regions] in the form of higher prices for manufactured goods and from the periphery to the national treasury in the form of customs duties.”

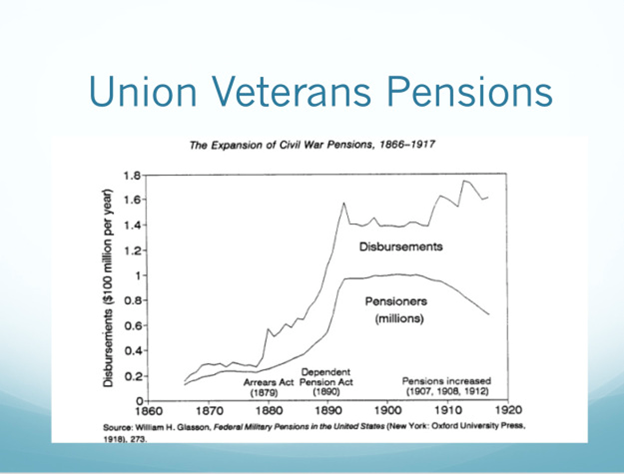

Finally, former Confederates derived no benefit from liberal federal spending on Union veteran pensions. Such pensions were originally paid only to soldiers who received disabling injuries during military service, but Republicans gradually expanded eligibility to solidify veterans as one of the Party’s voter constituencies. By 1904 any Union veteran over age 62 was regarded as disabled thereby transforming the program into an old age retirement system. In 1893 the pensions represented over 40% of the federal budget. Annual disbursements did not peak until 1921, which was 56 years after the War had ended. Payments were still being made as late as 2016.

While some federal spending not specified in the preceding table did benefit the South, they were few, tiny, or funded by the Southerners themselves. From 1865 – 1873 the federal government spent $103 million on public works, but less than 10% went to the former Confederate states.

Additionally, the federal government taxed cotton. As prices dropped after the war the levy represented as much as 25% of the selling price. It raised $68 million, which was about seven times the amount of public works spending in the South from 1865 to 1873. The tax could not be passed along to buyers since most American cotton was exported where it had to compete on World markets with cotton from other countries that had no such tax. The British, for example, could buy Egyptian or Indian cotton instead of American cotton if Southerners tried to pass the tax along to British buyers.

While the Freedmen’s Bureau provided some economic assistance, it was mostly devoted to ex-slaves. Moreover, the cotton tax alone was enough to pay for all the federal spending on the Bureau during the Bureau’s entire existence.

To clarify how post Civil War bank regulations retarded Southern economic recovery it should be understood that the U. S. Constitution only granted the federal government the authority to coin money, not to print fiat currency. Due to the collapse of the earlier Continental Dollar this was no mere oversight. In contrast, money could be coined from metals such as gold and silver that had intrinsic bullion value.

Nonetheless, the enormous federal financing required by the Civil War compelled monetary changes. The first was the 1862 Legal Tender Act, which paved the way for the 1863 National Banking Act. The first act authorized the federal government to print paper money without gold backing and the second forced national banks to become regular buyers of federal bonds, which were used to finance the War. The new “national” banks became eager buyers of government war bonds because the bonds could be used as interest-bearing reserves whereas gold reserves—the previous standard—paid no interest.

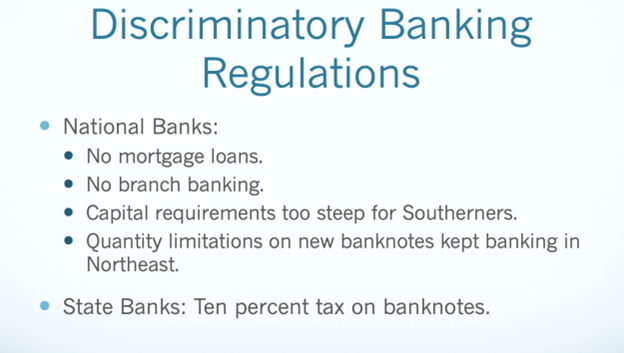

Although the post Civil War South badly needed re-building capital it was almost impossible for Southerners to organize suitable banks.

First, national bank capital requirements were beyond the means of poor Southerners. Second, national banks generally could not make mortgage loans, a loan type essential to the agrarian South. Third, national banks were restricted to a single branch, which was a handicap in the sparsely populated South. Fourth, even though state chartered banks might offer mortgages and/or require less start-up capital, the 10% federal tax on their banknotes burdened them with prohibitive operating costs. Fifth, regulatory limitations on the total value of national banknotes allowed to circulate throughout the country made it hard to gain authority to open new banks thereby leaving banking concentrated in the Northeast.

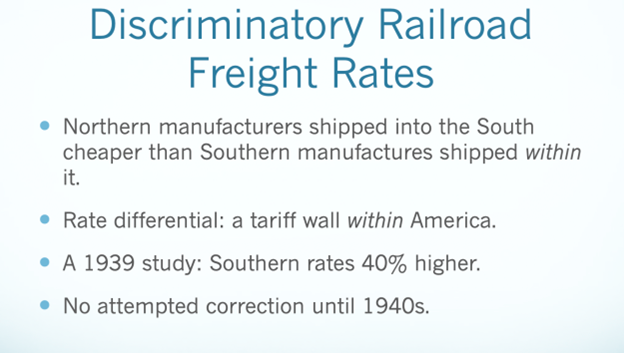

Northern railroads steadily increased their ownership of Southern operators for decades after the war due to a Southern capital shortage. Once under Northern control, the railroads quickly began using discriminatory freight rates to block Southern competition to principal Northern shippers such as steel makers.

When asked in 1890 why shipping rates into the North for Southern iron products was higher, one Pennsylvania Railroad agent replied, “It was done at the request of the Pennsylvania iron men.” Yet due to its wealth and industrial concentration, the region north of the Ohio and Potomac rivers was a key market. All domestic manufactures needed to access it if they were to compete on a national scale. As a means of impeding competition from Southern and Western manufactures the discriminatory rates were as effective as protective tariffs, which were constitutionally prohibited between states.

Interstate railroad freight practices were not subject to federal review until the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) was formed in 1887. Almost from the beginning, however, the ICC sanctioned discriminatory regional rates. No careful study was made until 1939 when rates for the same service in the South were found to be 40% higher than in the North on fourteen selected items. The differentials were so discriminatory that remote Northern manufactures could ship finished goods into the South at lower cost than Southern makers of the same items could distribute them within their own region.

Finally, the 1940 Transportation Act required the ICC to investigate and eliminate geographically discriminatory rates. After four years, in June 1944, the ICC ordered that rates in the North be increased by 10% and that those in the South and West be reduced by 10%.

Southern hostility toward protective tariffs was also indirect opposition to monopolies because such tariffs were a prime cause of monopolies.

The first federal response to monopolies was the 1890 Sherman Antitrust Act. Unfortunately, the act targeted only the apparatus of monopoly instead of the cause. Nine years later the president of New York based American Sugar Refining Company, which controlled 98% of the market through its still-famous Domino brand, admitted in testimony to an industrial commission:

The mother of all trusts is the customs tariff bill . . .

[Production economies of scale] . . . in the same line of business are a great incentive to [trust] formation, but these bear a very insignificant proportion to the advantages granted in the way of protection under the customs tariff . . .. . . It is the Government through its tariff laws, which plunders the people, and the trusts . . . are merely the machinery for doing it.

Tariffs bred monopolies like swamps bred mosquitoes. The era’s biggest, United States Steel, was deliberately formed to suppress competition. Even though steel could be produced more cheaply in America than in other countries, U. S. Steel sold products overseas at lower prices than domestically. Wire nails, for example, sold domestically at $2 per hundredweight, compared to $1.55 in Britain.

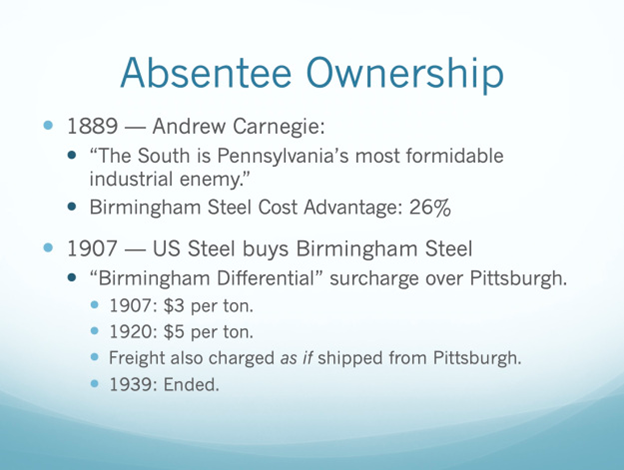

When Andrew Carnegie toured the emerging Southern steel industry centered in Birmingham in 1889, he declared, “the South is Pennsylvania’s most formidable industrial enemy.” About ten years later Carnegie’s mills merged into Pittsburgh-based U. S. Steel. Six years later U. S. Steel bought the biggest Southern mills and imposed discriminatory pricing on Southern production. Thereafter, steel from the company’s Alabama mills included an incremental mark-up, termed the “Birmingham Differential,” of $3 per ton over the Pittsburgh quote.

To further penalize Alabama production, buyers of Birmingham steel were required to pay freight from Birmingham plus a phantom charge as if the shipments originated in Pittsburgh. After Woodrow Wilson became President a Federal Trade Commission (FTC) investigation concluded that Birmingham’s steel production costs were the lowest in the country and 26% below those of Pittsburgh. Yet U. S. Steel continued to require a $3 per ton “Birmingham Differential,” which was raised to $5 after 1920. Six months after the differential was finally abolished in 1939 shipbuilding plants in Pascagoula, Mississippi and Mobile, Alabama announced major expansions.

President Roosevelt’s 1938 study revealed that absentee ownership was a protracted problem and included such essential industries as electric utilities, railroads, steel manufacturing and even cotton textile mills. Outsiders also controlled most of the area’s natural resources such as coal, feldspar, iron ore, zinc, sulfur, and bauxite. Northerners reserved for themselves the more prosperous work of converting such raw materials into finished goods.

About 90% of the 4.5 million American blacks at the end of the Civil War were living in the former Confederate states. The great majority were illiterate ex-slaves needing public education. Although the federally financed Freedmen’s Bureau spent over $5 million for black schools after the Civil War, Southerners basically paid for the schools through the cotton tax noted earlier. After Congress discontinued the Bureau in 1870, the former Rebel states had to rely upon their own meager tax resources to pay for educating all their pupils, including the 40% who were black.

In sum, while Reconstruction history should include a thorough analysis of racism and its protracted effects, contemporary historians should also devote comparable attention to the numerous equally important non-racial political and economic factors. An entire chapter in my Southern Reconstruction book is devoted to an analysis of the region’s racial adjustments. As noted, however, this speech was limited to non-racial factors because nearly all of the books on Reconstruction during the past thirty years are race-centric.